NLA CATALOGUE NOTES (incorrect information)

nla.pic-vn4269870 PIC P1029/14 LOC Album 935 Thomas Francis, Ly. [i.e. Lady] Franklin 4, taken at Port Arthur, 1874 [picture] 1874. 1 photograph on carte-de-visite mount : albumen ; 9.4 x 5.6 cm. on mount 10.5 x 6.3 cm. Part of Convict portraits, Port Arthur, 1874 [picture]

Hundreds of these 1870s mugshots of Tasmanian prisoners were transcribed and displayed in museum exhibitions in Tasmania between 1915 and 1934 with the generic date "1874" and place "Port Arthur" regardless of each prisoner's individual criminal history, some of whom had never been incarcerated there. The National Library of Australia catalogue note records only what was written on the verso of this and dozens of other photographs in their collection of the so-called "Convicts, Port Arthur 1874" when they were acquired by donation in Canberra in 1964 (Dan Sprod papers NLA MS 2320 1.5.64 Missionary history) and in 1985 (per interview with John McPhee, NPG, 1984). Most of these photographs are duplicates made by T. J. Nevin from his negative of a single sitting with the prisoner, taken for use by police.

Thomas FRANCIS was photographed by T.J. Nevin, the only photographer and the only commercial photographer contracted to the Municipal Police Office and Attorney-General's Office in the early 1870s to provide the police with prisoner identification mugshots. The photograph was taken at the MPO, Hobart Town Hall, between the 2nd and 6th February 1874, and not at the Port Arthur prison. This prisoner was one of three men photographed on that date: John MORAN and Thomas SAUNDERS were also discharged and photographed in Hobart by T.J. Nevin between 4th-6th February 1874. The carte-de-visite of Moran is held at the National Library of Australia, and a print from Nevin's original negative of Moran is held at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery. The cdv of Saunders is also held at the QVMAG:

[Above and below]:

John Moran, photographed on discharge by T.J. Nevin at the MPO Hobart Town Hall on 6th February 1874. The print from Nevin's glass negative of John Moran is held at the QVMAG; the cdv in an oval mount is held at the NLA.

[Above]: Thomas Saunders, photographed on discharge at the MPO Hobart Town Hall by T.J. Nevin on 6th February, 1874. This cdv is held at the QVMAG and numbered recto "133" in the late 20th century when the QVMAG copied hundreds from their collection for dispersal to the Archives Office and Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart .

POLICE RECORDS

[Above]: the first police gazette notice for Thomas Francis (and John Moran), received from Port Arthur and discharged between 31st January and 4th February. No physical details were recorded for either prisoner.

Source: Tasmania Reports of Crime Information for Police, Gov't printer.

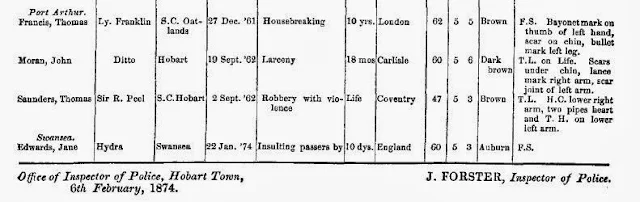

[Above]: the second police gazette notice of Thomas Francis (including John Moran and Thomas Saunders), discharged from the Office of Inspector of Police, Hobart Town, dated 6th February 1874. Full physical details were transcribed and gazetted only after Thomas Francis (and John Moran) reported for discharge, and received an FS on discharge - Free in Servitude - in Francis' case, and a TL - ticket of leave - in the case of Moran and Saunders. All three men - Thomas Francis, John Moran and Thomas Saunders - were photographed by Thomas J. Nevin at the Office of Inspector of Police, which was located in the Hobart Town Hall no later than the 6th February and no earlier than the 31st January - 4th February 1874, in Hobart, and not at Port Arthur.

DO NOT BELIEVE WHAT YOU READ or HEAR from Edwin Barnard

Edwin Barnard claims to be the author of a recent publication sponsored by the National Library of Australia titled Exiled: The Port Arthur Convict Photographs (Edwin Barnard, NLA 2010).

This extract about the photograph of Thomas FRANCIS appears on page 83 of Exiled: The Port Arthur Convict Photographs (Edwin Barnard NLA 2010).

There is not much that is authentic or even sincere about this book. The "story" as told by Barnard is from the viewpoint of the benign coloniser. The author claims (on back cover) not to have convict heritage, but as if to reassure those who do, he lives in hope of finding one in his family one day (yeah, right). Barnard's previous publication is generically very similar: a Reader's Digest of "Antarctica: great stories from the Frozen Continent."

See this critique of the book by Tim Causer (2011) Bentham Project, University College London.

Interviewed on ABC radio (twice) in October 2010 (Radio National 14 October 2010; RA W.A. Port Hedland ) Barnard stated that he merely "stumbled across" these Tasmanian prisoner photographs, omitting to mention, of course, that they had been online at the NLA and the Archives Office of Tasmania for more than a decade (since the 1990s at the National Library), and that he had made ready use of the original research we have provided here online (since 2005) about each photograph. One of the first we documented and discussed was that of prisoner Denis Dogherty (because of Anthony Trollope's account) yet listening to Barnard - who chose to talk at length about Dogherty - you would believe that he alone had unearthed these fascinating facts, such is Barnard's tenor and "excitement" . When asked who photographed the prisoners, his answer was even more disingenuous if not downright arrogant - he failed to mention Nevin by name, dismissing him simply as "some guy" who was a commercial photographer. Yet Barnard's primary source of information about Dogherty was from a page copied from Geoff Lennox (1994), held in Thomas J. Nevin's Photographer File at the National Library of Australia:

NLA CATALOGUE

[Nevin, T. J. : photography related ephemera material collected by the National Library of Australia]

Bib ID 3821234

Dogherty's photograph attributed to T. J. Nevin

Held at the NLA in Nevin's file

Photo taken at the National Library of Australia, 6 Feb 2015

Photos copyright KLW NFC 2015 ARR

Interviewed again by ABC TV journalist Siobhan Heanue on 22 February 2011 (video on page) and filmed at the NLA with the prisoner mugshots laid out before him, Edwin Barnard repeated the egotistical nonsense that he "discovered" and "unearthed" the convict photographs. Note Siobhan Heanue's error when she states in the video prologue that these mugshots "were taken in the 1850s at Port Arthur" - a comment which betrays ignorance of the historical subject she is reporting.

The release at this time of this book, Exiled: The Port Arthur Convict Photographs (2010) would lead the public to believe the authors (Edwin Barnard with Hamish Maxwell-Stewart) have published the latest word on the 84 mugshots of Tasmanian prisoners - or to use the NLA's aesthetic term - "convict portraits" - held at the NLA, the majority of which were exhibited there correctly in 1982/1995 and placed online as photographs taken by professional photographer and civil servant Thomas J. Nevin, complete with verso inscriptions, However, as we have painstakingly demonstrated here with original police records and with other archival documents and newspaper accounts on these Thomas J. Nevin weblogs, these prisoners were photographed by Thomas J. Nevin and his brother Constable John Nevin at the Supreme Court Hobart, the Hobart Gaol, and the MPO Hobart Town Hall between 1871 and 1884. Edwin Barnard's research is far too generalized, already out of date, and of no use to photohistorians. As an author, Edwin Barnard has little credibility and should not be referenced as an authority.

On page 83, the so-called "author" of Exiled: The Port Arthur Convict Photographs erroneously states that Thomas Francis was released in March 1875, and that he was 58 years old. Thomas Francis was released on 6th February 1874, and was 62 years old, per police records. Who are you going to believe? The original police record which you can actually SEE here or a vague statement in a glossy vanity publication? And the publication is all vanity and bleeding heart for men who were essentially habitual criminals, whose second and repeat offences, in many cases involving rape and murder, earned them a further term of imprisonment and a mugshot by Nevin at the Hobart Gaol. Would men with similar criminal records from the 1970s receive the same loving treatment? Of course not. Yet the 1870s prisoner photographs were taken for the same reasons and in the same circumstances as those dictated by police regulations today.

Edwin Barnard and the book's historical consultant Hamish Maxwell-Stewart (both British-born, the latter an academic who is best described as the tail wagging the dog with the misinformation he is intent on spawning about Nevin's attribution) of Exiled: The Port Arthur Convict Photographs have a barely concealed agenda: to encourage the reading of criminality by viewers into a man's physical features, mediated with text and image amidst the echoes of phrenology and the malodour of eugenics. The cliched association of the term "PORT ARTHUR" with these prisoners' mugshots is the honeypot trap with which the authors hope to attract readers.The accompanying biographical narrative to each man's image was mustered by the authors from transportation records, from a few newspaper articles and from a few earlier publications. Information which we had chosen not to publish on these weblogs also appears as lacunae in their book. The tenor of the biographies is one which pleads to forgive these men, to see them even as “pioneers” - a laughable notion. They were pioneers of crime for the police, certainly, because they were habitual offenders and recidivists with long criminal careers, but little else. Each man's entry is plumped up with irrelevant colorful graphica to render the whole product as an unproblematic, glossy coffee-table paperback aimed at children. Pages decorated with a lot of pretty paintings bear little if any connection to the prisoner's photograph despite the claim that the book ostensibly deals with PHOTOGRAPHS, i.e. objects which are nothing more than cardboard artefacts and only recently acquired by a national institution, the National Library which has its own history of misuse and abuse of these items, but which - as photographs - had a real history of PRODUCTION in the hands of their PRODUCER, the very real photographer T.J. Nevin. A more appropriate title for this book would be:

OUTCASTS: Biographies of 55 Transported Convicts to Van Diemen's Land, with later police photographs taken by T.J. Nevin.

There is no guarantee that the man in each photograph in this book belonged to the name assigned to him, and that is a real dilemma for anyone wishing to trace their convict ancestry. A case in point involves the descendants of businessman Henry Jones, founder of IXL Jams, who have been led to believe that the mugshot of prisoner Elijah Elton (pp 161-171) who used the alias John Jones, was their ancestor.

These photographs originally taken by Nevin were either loose duplicates or those removed from the criminal's prison record sheet and Hobart Gaol registers ca. 1915, probably by Edward Searle and John Watt Beattie, who salvaged them from the Sheriff's Office at the Hobart Gaol to display them in Beattie's "Port Arthur Museum" in Hobart. They reproduced prints from Nevin's original glass negatives, according to a visitor from South Australia in 1916, and copied others including the cdvs, which were acquired by the QVMAG on Beattie's death in 1930. Beattie had full government endorsement when Port Arthur, renamed as Carnarvon, was heavily promoted interstate as Tasmania's premier tourist attraction, These mugshots catered to the tourist's contemporary fascination with character typologies, phrenology and eugenics, and the Tasmanian "stain".

The handwritten transcription across the versos of many of these prisoners' photographs - "Taken at Port Arthur 1874" was the work of the second archivist to catalogue the collection sometime between 1915 and 1934. The first archivist, whoever that was, who began organizing these cdvs printed in oval mounts into a collection just before 1915 and probably to make copies, omitted any reference to Port Arthur, i.e. "Taken at Port Arthur" does NOT appear on the versos of the first three cartes numbered 1 to 3, those cartes of prisoners George Nutt, William Yeomans and Bewley Tuck. Port Arthur was not the main place of incarceration by July 1873: just 40 prisoners were left there when the report on closure of the prison was tabled in Parliament on 15th July 1873 and those prisoners were returned to Hobart by late 1873. Nevin had already photographed sixty (60) transferees from Port Arthur by that date, some previously as early as 1871 at their Supreme Court trials in Hobart before they were sent to Port Arthur. The constant mantra about these photographs being "portraits of Port Arthur convicts" is completely misleading. Read the meme in the title - "PHOTOGRAPHS" - they were police photographs taken for and used by the Municipal Police Office, Hobart in the course of daily surveillance and prosecution.

Above: page 12, Exiled, with recto and verso of carte of prisoner Thomas Francis, photo by T.J. Nevin, 6th Feb. 1874.

The number "231" written on the verso of this carte is NOT a number allocated to the prisoner, as the note above suggests: it is the number used by the copyist and cataloguist in the early 1900s for archiving, and for exhibiting in the 1934 exhibition to commemorate Beattie's bequest to the Launceston City Council and Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston,

Attractive but by no means accurate, this publication called Exiled: The Port Arthur Convict Photographs (Barnard 2010) creates more problems that it resolves and no doubt that is the result hoped for by the supporters of the fantasy about the non-photographer A.H. Boyd. The notes about Thomas J. Nevin on page 15 prevaricate upon his unique legacy with the usual idiocies about the non-photographer A.H. Boyd quoting the desperate and deliberate falsifications from the lamentable and covetous Julia Clark. Many phrases from these Nevin weblogs can be traced throughout the texts, both the general notes and notes specific to each photograph, yet no courtesy request was received by us from Edwin Barnard or the NLA. The information one would expect in such a book with such a subtitle "The Port Arthur Convict Photographs" should include a biography of the photographer (Nevin's has been online since 2005), the types of cameras he used, his studio practice and assistants, his methods of producing a carte-de-visite in an oval mount from his glass negative, government documents detailing his contractual engagement and civil service, the police requirements and judicial regulations, and all the rest about the reproduction, copying and distribution of Nevin's prisoner photographs by later photographers and archivists from the early 1900s. Those key topoi have unfolded on these Thomas J. Nevin weblogs since 2005 and are exclusively copyrighted to the weblog authors.

Note on Thomas J. Nevin, p.15, Exiled; The Port Arthur Convict Photographs. the possibility that not only Thomas Nevin but also his brother Constable John Nevin at the Hobart Gaol worked for police as police photographers does not cross the author's mind.

For these reasons, any attempt by the National Library of Australia in this publication (or any other) at the diminishment of Nevin's technical and official achievements as the only police photographer of the 1870s (assisted by his brother Constable John Nevin) who produced these prisoner photographs in Tasmania has to be viewed in the context of the fishbowl politics of the National Library of Australia. In other words, Edwin Barnard's claims that he has written a book about PHOTOGRAPHS are irrelevant in the context of the history of police photography. The rest of the world's assessment of T.J. Nevin as "the photographer of the earliest surviving Australian prisoner mugshots" is more than ever consolidated by the NLA's failings as a result.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

[Above]: pages 82- 83, Exiled; The Port Arthur Convict Photographs (NLA 2010) with errors about the prisoner Thomas Francis. Photos copyright © KLW NFC 2010 ARR.

Summary

RELATED posts main weblog

- Fraudulent pretensions

- Margaret Glover and the fabrication of photohistory

- Working with police and prisoners

- The A.H. Boyd misattribution at DAAO

- About those photographic glasses 1873

- Nepotism, corruption and Port Arthur 1873

- The QVMAG, Chris Long and A.H. Boyd

- "In a New Light": NLA Exhibition with Boyd misattribution

- Nevin's mugshots: the transitional pose and frame

- Anne-Marie Willis & Richard Neville on the Boyd misattribution

- Three significant prisoner cartes by T. J. Nevin

- Helen Ennis’ NLA publication ‘Intersections’ 2004

- Isobel Crombie and Helen Ennis: how misattribution can persist

- Laterality: Helen Ennis & the poses in Nevin's portraits

- A Question of Stupidity & the National Library of Australia

- Prisoner Elijah ELTON aka John Jones and 'Flash Jack'