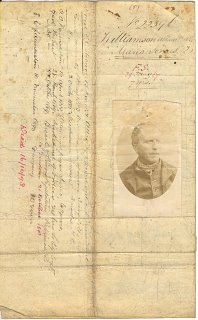

These cartes-de-visite prisoner identification photographs were produced on government contracts under tender and paid on commission to photographer Thomas J. Nevin who combined commercial practice with civil service and service to the police as special constable and prisons photographer. The earliest date from 1872, the later ones date to 1886, taken with the assistance of Thomas' brother Constable John Nevin at the Hobart Gaol. The photographs on glass negatives were printed in cdv mounts as conventional studio portraits, small enough to be pasted to the prisoner's record. The majority were taken at the Hobart Town Gaol on the occasion of the prisoner's sentence at the Supreme Court, or if sentenced in Launceston, on being "received" from a regional court. The "booking photograph" of the man in street clothes was taken on arrest, or on discharge and release. Most of the extant NLA photographs were taken of transported men (i.e before 1853) who had re-offended and were habitual criminals by the 1860s and 1870s, and were sentenced again to lengthy terms, many as absconders, some as rapists, murderers, and burglars.

Thomas J. Nevin used the same format as commercial photographer Charles Nettleton in Victoria in the 1870s to photograph prisoners (e.g. his Ned Kelly and Lowry prisoner identification cdv's): a half body shot of the prisoner, his sightlines to the left or right side of frame, produced in sepia and even hand-coloured in some examples of Thomas Nevin's prisoner cdv's ), and printed in an oval mount. The original capture on a glass negative was printed as either uncut or mounted as cdv, the latter pasted to the prisoner's rap sheet with duplicates circulated to regional police where the prisoner was sent to work.

Photo historians in recent years have judged these 1870s Tasmanian prisoner cdv's in terms that either attempt to aesthetise the photograph as an art history artefact (Chris Long, 1995), and therefore expect all the versos to display a studio stamp, for example, or situate them within a discourse of eugenics in similar manner to the appraisal of collections of Aboriginal portraits. In the 1990s some have attempted to impose a postmodern Marxist interpretation to underscore differentials of power and class, notably Isobel Crombie (2004) after Helen Ennis, (2000).

A recent example of postmodern discourse applied to Thomas Nevin's "convict portraits" was published as these statements by Helen Ennis (2007):

Helen Ennis

ABC TV snapshot 27 August 2010

Helen Ennis comments on pages 21-22:

Within the field of portraiture Australia was no exception in addressing the needs of the state. In 1874 the last remaining convicts and paupers at the Port Arthur penal settlement in Tasmania were photographed according to a set formula; each man was placed in front of a neutral background and photographed in three-quarter view. In contrast to the standard commercial portrait in which eye contact was a key component, the convict did not face the camera. His averted gaze reinforced the unequal power dynamics in the relationships between the subject and the photographer and also between the subject and the relevant authorities. These are photographs in which those photographed are assumed to have no personal or emotional investment; presumably the convicts never saw the final prints over which they had no claim.

Click on images for large view

Helen Ennis, pages 21-22 ,

Exposures: Photography and Australia, Reaktion Books London 2007

None of these interpretative approaches has examined the context and tenor of the interpersonal relationship between the jobbing photographer (in this case, T.J. Nevin) and the prisoner who sat in front of him, and none to date has applied an empirical study of portraiture poses to the examination of these prisoner photographs. Nor indeed has any commentator attempted to contextualise the photographs with prisoner records, Treasury and Supreme Court documents, or indeed with comparisons to Nevin's other photographic portraits such as those of family members, private clientele, and public figures taken before 1880 currently held in public and private collections.

After the mid 1880's, the poses changed; the Bertillon method was introduced into prison photographic practice in Tasmania as elsewhere.

THE BERTILLON METHOD in Tasmanian prisons 1900s

Women prisoners 1910: State Library of Tasmania eHeritage Collection

The photographs of these two women were taken in Tasmania according to the conventions of the Bertillon Method - one in profile, one full frontal. Alphonse Bertillon's system of criminal anthropometry (example below, 1888) included taking measurements of the individual which were recorded on a card accompanying the photograph:

Self-portrait: Alphonse Bertillon's measurement card,

done according to his own system for criminal anthropometry

Date: 1888

Source: University College London, GP, 137/13

By contrast, the early examples of prisoner identification photographs taken by Thomas J. Nevin in the 1870s show a consistent pattern of the subject seated, with sightlines to either the left or right side of the frame. The final image pasted to the record was framed in an oval mount. This mid-Victorian convention of portraiture is also evident in Thomas Nevin's vignetted upper-body portraits of his own family members including himself in one self-portrait used as an ID photograph when visiting prisons and courts, and of his private clientele, including his patron and referee Attorney-General W.R. Giblin, where the subject's sightlines are diverted to lower left or right of frame. This pose was conventional; it was a commercial technique applied by Nevin to his commission for the 1870s convicts' identification photographs as well.

The pose was not the result of the social status, class and power differentials between photographer and convict, as Helen Ennis suggests (Exposures, Photography and Australia, 2007, pages 21-22), a suggestion which ignores this pattern in Nevin's technique; which assumes that Nevin was not familiar, nor even friendly, with these convicts, some of whom had travelled as Parkhurst boys with Thomas Nevin, aged 10, and his family to Tasmania in 1852 on board the Fairlie, eg. Michael Murphy; and which presupposes that at the point of capture (always dated at 1874 in the way the NLA has catalogued these as a series) , the convict was cowering under the gaze of a punitive individual such as the Commandant of the Port Arthur prison, A.H. Boyd, a furphy [erroneous story] created by Chris Long which has resulted in confusion and systemic misattribution, and has misled Ennis into publishing a statement that is coloured by such underlying misconceptions:

... In contrast to the standard commercial portrait in which eye contact was a key component, the convict did not face the camera. His averted gaze reinforced the unequal power dynamics in the relationships between the subject and the photographer and also between the subject and the relevant authorities. These are photographs in which those photographed are assumed to have no personal or emotional investment; presumably the convicts never saw the final prints over which they had no claim.[Helen Ennis, 2007:21-22]Most of the convicts pictured in the NLA collection were photographed at criminal sittings of the Supreme Court or on SC arraignment, and many were photographed again at the point of discharge in Hobart. Why would those facing discharge be be cowering? The prisoner's "emotional investment" would have been relief at being released. And he would have seen the photograph taken of him, as the same photograph was on his record when he routinely had to report to the Town Hall Municipal Police Office as an ex-convict on release with various conditions. Prisoner photographs were also displayed to the public in the police office rogues' gallery in the event of a warrant issued for arrest. There are no facts, or substance or proof supported by original documentation behind Ennis' statements; worse, there is no understanding of the contexts in which police functioned. Instead, she gives an appraisal that is void of documentation, and full of the gaze of the late 20th century art historian.

The net effect is that these "mugshots" of Tasmanian prisoners have become "PORTRAITS" in her terms, merely aesthetic objects with a photographic misattribution to an alleged Sunday amateur suggested by propinquity alone to prisoners as A.H. Boyd was while Commandant at Port Arthur (May 1871-December 1873). Boyd had no reputation as a photographer in his lifetime, no official documents exist which associate him as a photographer of prisoners, and no works by him are extant, as the perpetrator of this "belief" about Boyd, Chris Long, now readily acknowledges. But to caress the postmodern discursive turn of power differentials into existence, these Boyd fantasists needed a man in power to conform to their thesis. Helen Ennis also advises the NLA (In a New Light exhibition 2000-3), and her influence continues to inform their absurd inclusion of Boyd's name on their Tasmanian convict photographs' full records. It's a legally questionable state of affairs which compromises the national heritage as a fictional reinvention because of a few "professional" commentators' anxieties about protecting their reputations in the face of a very obvious error.

Thomas Nevin's "convict portraits", posed and produced within conventional commercial studio portraiture techniques of the 1870s which are held at the NLA were taken in the Hobart courts, the Town Hall Police Office and the Hobart Gaol, and not at Port Arthur where sixty prisoners of the criminal class had already been transferred to Hobart by late 1872, and the remaining few by mid 1874 (tabled in the Parliament by A-G Giblin, July 1873). The NLA examples were acquired from a variety of sources, whether as government estrays donated by Dr Gunson in the 1960s, or as originals and duplicates forwarded from the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in 1982-1985. It was not until the late 1880s that the Bertillon method became standard prison photographic practice in Tasmania, by which time both Nevin brothers had ceased professional photographic practice.

Prison record of convict Williamson with carte T.J. Nevin still pasted to the parchment record, courtesy of the PCHS and State Library of Tasmania, eHeritage collection.

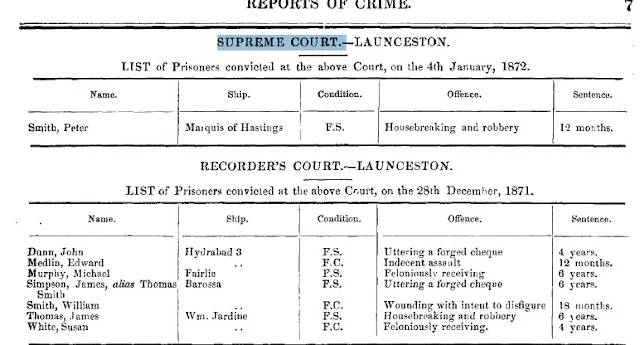

Michael Murphy per the Fairlie 1852,

sentenced to 6 yrs at the Supreme Court Launceston 1871

photographed by T. J. Nevin on transfer to the Hobart Gaol 1871.

Originals taken by Nevin and copies held at the QVMAG Ref: 1985:P0120, and at the AOT, Ref: PH30/1/3217) "Tasmanian [Port Arthur] convicts photographs by Thomas Nevin" courtesy of the Archives Office of Tasmania.

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH

In this interview with Robyn Williams, Mike Nicholls puts the asymmetries of posing into historical perspective:

The expressive side of the face

Source: ABC Radio National Science Show 12 July 2008

TRANSCRIPT of interview

60% of people turn their head when asked to pose for a portrait. A prime example is that of Mona Lisa. So why does this bias exist? When people try to express emotion, they turn the left side of the face.

Mike Nicholls: Well, like most portraits, she's facing so that the left side of her face is showing more than the right side of her face. A few years ago a survey was done of portraits going from 1300 right up until now, and around about 60% of the portraits are turned so that they're featuring the left side of the face.

Robyn Williams: Why is that significant?

Mike Nicholls: I guess it's interesting, it could be either way. If you think about the face, it's pretty well symmetrical to look at, and it's interesting that this bias exists, and it makes you wonder why and whether it's the model choosing to do that or whether it's in actual fact the artist choosing to portray the left side of the face.

Robyn Williams: And what do you think, personally?

Mike Nicholls: There's a number of options. It could be to do with the handedness of the artist. Most artists are indeed right handed, but in actual fact if you look at the work made by left-handed artists you still get the same bias, and indeed if you look at photographic portraits you get the same bias. So it's not something simple to do with handedness.

Robyn Williams: Leonardo, by the way, was left-handed, wasn't he?

Mike Nicholls: Yes, that's right. So you always hear there's more left-handers amongst artists but in actual face when you look at the hard data there's not much there, most of them still are right-handed.

Robyn Williams: Tell me, what have you been doing to study this phenomenon?

Mike Nicholls: We wanted to get to the bottom of this and so actually we wanted to see if it was the artist determining the bias or whether it's the model themselves. So we had a bunch of university students sit down and we got them to pose in two ways. In one condition we said to them, 'This is a portrait, you're an important scientist and it's going to hang in the Royal Society gallery, but you don't want to look smug or proud,' so we had them trying to conceal their emotion and not show any emotion at all.

In the second condition we had people posing and in this case said to them, 'It's a portrait for your family, you want to show your love and as much emotion as you can,' so we've got an emotional condition and a non-emotional condition. We then had people pose simply for the portrait and we took their photograph. What we found was that in the non-emotional condition there was no bias, people didn't tend to turn one way or the other, but when people were trying to express their emotion they turned the left side of their face, like most portraits indeed do.

This is interesting because it ties in with the fact that females in general are more likely to turn the left side of the face when having a portrait taken than males are, and you wonder why that is. It's most probably because most females are showing more emotion, they're naturally more emotional than males, and so it most probably reflects that.

Robyn Williams: Of course Professor John Bradshaw from Monash in Ockham's Razor did describe this laterality in the face in terms even of newsreaders who were rather more significant if you watch their faces on the right-hand side when they were speaking. So you address the right-hand side to get information, and the left-hand side, as you were suggesting, is more a kind of emotional signaller. Does that make sense to you?

Mike Nicholls: I think it does boil down to what the two sides of the brain are doing. So when people are turning the left side of the face, the left side of your face is indeed controlled by the right side of your brain, and your right side of the brain is dominant for the expression of emotion. So when we smile, when we look fearful, we tend to do it slightly more strongly on the left side of the face. So it suggests that people somehow know that the left side is more emotionally expressive, and indeed they're turning that side.

And in contrast, as you were saying, while the left side might be

more important for emotional expression, the right side is more important for verbal expression. So when we're lip-reading it seems...and you can see this in newsreaders all the time, look at the right side of the mouth, it's generally the side which is moving more and that's because the right side of the mouth is controlled by the left side of the brain.

Robyn Williams: I had no idea I actually looked at a mouth except full on. I can't imagine just looking at one little part of it, but we do apparently.

Mike Nicholls: Yes, that's right. With the research I did with John we were looking at which side of the mouth people do look at, and not only do we move the right side of the mouth but when we're actually looking at someone trying to lip-read we attend to that side of their mouth more as well.

Robyn Williams: Why is this sort of thing important, do you think, this sort of study?

Mike Nicholls: I think its interesting. Symmetries are naturally interesting. We could so easily, like most other animals, be symmetrical. Most other animals are for the most part, at least in terms of the way their brain is organised, fairly symmetrical. There are exceptions too; things such as birds can have quite asymmetrical brains. But of the mammals we have the most asymmetrical brain. So I guess it gives you an insight into what it is to be human and how important it is for the brain to be asymmetrically organised in its function.

Robyn Williams: And how are you taking this next?

Mike Nicholls: We're moving on to looking at asymmetries in attention and how we pay more attention to one side of the space, and we recently were looking at collisions and finding that people collide more on one side. We over attend to the left and are more likely to collide with things on our right.

Robyn Williams: How worrying!

Mike Nicholls: Yes, it could have quite a lot of real life impact. We've been getting people to get in a wheelchair and negotiate an obstacle race and find that people do collide more to the right-hand side, and that happens whether they're walking, in a wheelchair or whatever. But it could have quite a few implications for manoeuvring ships. The Lake Illawarra, when she hit the Tasman Bridge down in Tasmania, she hit to starboard, so there could be...if you start to look at the incidence of these collisions, they may be asymmetrical.

Guests

Mike Nicholls

University of Melbourne

https://www.psych.unimelb.edu.au/people/staff/NichollsM.html

Presenter

Robyn Williams