AWOL SEAMAN Henry Geeves, January 1851

H.M.S. HAVANNAH at Hobart etc December 1850-January 1851

AUTHOR Godfrey Charles MUNDY in Hobart 1850-1851

H.M.S. Havannah 1812

Source: Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Havannah_(1811):

H.M.S. Havannah 1812

Source: Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Havannah_(1811):

HMS Havannah was a Royal Navy 36-gun fifth-rate frigate [948 tons]. She was launched in 1811 and was one of twenty-seven Apollo-class frigates. She was cut down to a 24-gun sixth rate in 1845, converted to a training ship in 1860, and sold for breaking up in 1905.

Henry

Geeves was an articled seaman, one of twenty-two (22) crew members who sailed from the Downs (UK) on 22nd August 1850 on board the barque

Rattler, 522 tons, Captain Edward Goldsmith in command, arriving at Hobart, Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) on 14th December 1850. Cabin passengers numbered seven, with four more in steerage. The return voyage of the

Rattler to London would commence on 19th March 1851, after three months at Hobart while Captain Goldsmith attended to his construction of the

twin vehicular ferry SS Kangaroo and the development of a patent slip at his shipyard on the Queen's Domain.

Henry Geeves, however, had no intention of joining the crew on the

Rattler's return voyage to London when he went absent without leave (AWOL) on 31st December 1850. He returned to the ship three days later for his clothes. Appearing as the plaintiff in the Police Magistrate's Court on January 20th 1851, his complaint against Captain Goldsmith was for wages which he claimed were due to him because he felt he had been discharged by the

Rattler's chief officer, having volunteered as an "old man-of-war's man" to join the frigate H.M.S.

Havannah when an officer from the

Havannah boarded the

Rattler seeking additional crew. Captain Goldsmith did not pursue the charge on the grounds that Geeves was never discharged from the

Rattler's crew in the first instance, and as he had not been accepted by the

Havannah, he was to return to the

Rattler.

The "Rattler" at Hobart, December 1850

Henry Geeves listed among crew:

Signature of Captain Edward Goldsmith on list of crew and passengers per Rattler from London, at Hobart, 26 December 1850. Crew listed by name: 22; passengers listed by name: 12, one more than was reported in the Mercury, 18 Dec. 1850, a T. B. Watern [?]

Source:Archives Office of Tasmania

Cargo, Passenger and Crew Lists

Customs Dept: CUS36/1/442 Image 203

Henry Geeves listed among crew:

Signature of Captain Edward Goldsmith on list of crew and passengers per Rattler from London, at Hobart, 26 December 1850. Crew listed by name: 22; passengers listed by name: 12, one more than was reported in the Mercury, 18 Dec. 1850, a T. B. Watern [?]

Source:Archives Office of Tasmania

Cargo, Passenger and Crew Lists

Customs Dept: CUS36/1/442 Image 203

Arrived the barque Rattler, 522 tons, Goldsmith from the Downs 26th August, with a general cargo. Cabin - Mr. and Mrs Cox, Mr and Mrs Vernon, Matthew and Henry Worley, C. J. Gilbert; steerage, Mrs. Downer, John Williams, Wm. Merry, Charles Daly.

Source: The Courier (Hobart, Tas. : 1840 - 1859) Wed 18 Dec 1850 Page 2 SHIPPING NEWS.

Customs House at London recorded on the

Rattler's Entry and Cocket documents a staggering quantity of spirits, beer, wine and alcohol-related products for duty-free shipment to Hobart on this voyage cleared on 22 August 1850 at London Docks, in all, sixty-seven cockets were signed by exporters and 530 listed items were cleared. Aside from the predominant cargo of alcohol, there was a case for the Governor of VDL, Sir William Denison; a box for the Royal Society; iron and coal from the Welsh "Iron King" William Crawshay II; and drugs from Mr. Lucas of Cheapside. There were transhipments too from Rotterdam ex-

Apollo of Geneva spirits, i.e. gin, the English word derived from jenever, genièvre, also called Dutch gin or Hollands, British plain malt spirits distilled from malt ex-

The Earl of Aberdeen, and Mr Cheesewright's cargo of Spanish and Portugal wine from Jersey in the Channel Islands. A quantity of this shipment of hogsheads of beer, casks and barrels of wine and spirits was bound for Captain Goldsmith's licensed wholesale business conducted jointly with brewer John Leslie Stewart at their premises, Davey Street, Hobart.

Without doubt, however, the most unusual consignments of this voyage were the

three 3yr old fillies purchased by John and James Lord from the bloodstock of the Duke of Richmond, Goodwood House, West Essex, UK, carefully tended by passengers Matthew and Henry Worley, immediate relatives of Hannah Lord nee Morley, the mother of John and James Lord. Their safe arrival was paramount, yet while the

Rattler was hove to in the River Derwent waiting for the Pilot to board, the departing barque the

Derwent, 404 tons, Harmsworth, master, was caught in a strong wind while attempting to "speak" the

Rattler. The

Derwent struck the

Rattler, carrying away the larboard gallery at the stern near the rudder. The collision resulted in repairs to both vessels and especially to the

Rattler which remained in Hobart at Captain Goldsmith's shipyard below the "paddock", the Queen's Park/Domain, until ready again for the return voyage to London on 19th March 1851. The

Cornwall Chronicle syndicated this report of the incident from the

Advertiser:

TRANSCRIPT

The Rattler, Captain Goldsmith, arrived on Saturday, after an average passage of 110 days, having left on the 26th August. She consequently brings no additional items of intelligence, but several intermediate papers. Capt. Goldsmith has on board three very fine blood fillies purchased by Mr. John Lord, from the stock of the Duke of Richmond. The fillies are three years old, and have arrived in first rate condition, sufficiently evidencing the care and attention which have been paid to them on the passage. One was purchased for Mr. James Lord, and the other two for Mr. John Lord's own stud. They will prove valuable additions to our stock, the Duke of Richmond's stock comprising the best blood of England. Captain Goldsmith, to whom the colony is much indebted for many choice plants and flowers, has brought out with him seven cases of plants this voyage, all of which are in good order. On coming up the river, the Rattler got into collision with the Derwent, and had her larboard quarter gallery carried away. The Rattler was hove to waiting for the Pilot to come on board, and the Derwent coming down with a fair wind came rather too close, for the purpose of speaking her, and struck her on the larboard gallery, carrying it away. — Advertiser.

Three blood fillies for the Lord brothers on board the Rattler

Source: The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 - 1880) Thu 19 Dec 1850 Page 920 SHIP NEWS.

Geeves v. Goldsmith

Was blame assigned to any crew member of either vessel for the collision? Nothing was reported, though the logs of both ships would provide important details, if they are at all extant and available to the public. Perhaps Henry Geeves felt himself culpable in some small way, hence the desire to leave the

Rattler. He gave no reason why he went absent without leave when he appeared in court on 20th January 1851, apparently having misrepresented himself to the officer of HMS

Havannah about being an experienced "old man-of-war man". Then again, life on board such an illustrious frigate as the

Havannah which had taken pirate ships in all the seas, salvaged wrecks and fought in great battles in the Napoleonic era, would be far more rewarding. For example, in July 1851, the crew of HMS

Havannah received a cheque for £52.10 from Messrs Smith, Campbell and Co. Sydney for floating and towing the wreck of the brig

Algerine to safety. Not to mention the glory of experiencing first-hand the pomp and ceremony of the vessel's VIP celebrity status, and the excitement of locals when arriving at port. Even in the tiny port of Hobart, the

Havannah officers and crew were living it up.

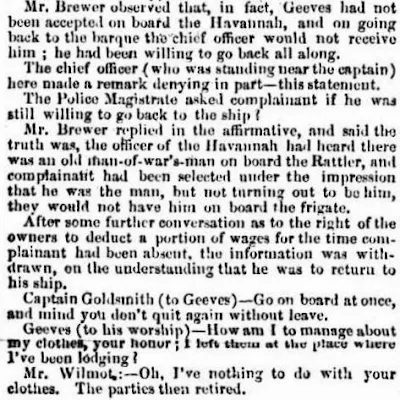

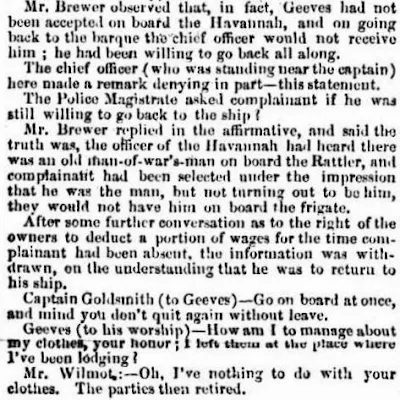

EXTRACT from Geeve's complaint against Captain Goldsmith

Extract: Police - Geeves v. Goldsmith

Britannia and Trades' Advocate Hobart Town, Tas: Monday 20 January 1851, page 2.

TRANSCRIPT

Extract: Police - Geeves v. Goldsmith

Britannia and Trades' Advocate Hobart Town, Tas: Monday 20 January 1851, page 2.

TRANSCRIPT

POLICE

A MAN-OF-WAR's MAN, - Geeves v. Goldsmith. - This was an information by an articled seaman of the barque Rattler, against Captain Goldsmith, for 7l, odd, amount of wages due on his discharge of the vessel. Mr. Perry appeared for the captain and owners; and Mr. Brewer, on behalf of complainant, arrived during the progress of the case.

After the reading of the information, and a plea of Not Guilty recorded, Mr. Perry made an objection to the proceedings on the ground that Geeves had not been discharged, and consequently still belonged to the Rattler. A long discussion here took place as to the circumstances under which complainant was alleged to have been discharged from the ship, when it appeared that an officer of H.M.S. Havannah, now in this harbour, came on board the Rattler, and mustered the men, when complainant volunteered for the frigate, and was desired to go board, the captain telling him that he might come back for his money and clothes if he passed muster for the Havannah. This was on the 31st December; and three days afterwards he returned and took away his clothes, since which he had neither been at work in the Rattler, nor the Havannah. Extracts from the log of the barque were read by Mr. Perry in proof of those facts; and that gentleman, on behalf of Captain Goldsmith, now demanded the plaintiff return to the Rattler, as it does not appear that he had been accepted in the Havannah.

Police Magistrate (to Geeves) - You must prove that you have been received into her Majesty's service.

Geeves said, Captain Goldsmith told him to quit the ship, and he had been refused permission to go back.

Mr. Perry was proceeding to cross-examine the claimant, and had proved the articles, when Mr. Brewer entered the court, and at Mr. Wilmot's request repeated the grounds of his opposition to the claim.

Mr. Brewer observed that, in fact, Geeves had not been accepted on board the Havannah, and on going back to the barque the chief officer would not receive him; he had been willing to go back all along.

The chief officer (who was standing near the captain) here made a remark denying in part - this statement.

The Police Magistrate asked complainant if he was still willing to go back to the ship?

Mr. Brewer replied in the affirmative, and said the truth was, the officer of the Havannah had heard there was an old man-of-war's-man on board the Rattler, and complainant had been selected under the impression he was the man, but not turning out to be him, they would not have him on board the frigate.

After some further conversation as to the right of the owners to deduct a portion of wages for the time complainant had been absent, the information was withdrawn, on the understanding that he was to return to his ship.

Captain Goldsmith (to Geeves) - Go on board at once, and mind you don't quit again without leave.

Geeves (to his worship) - How am I to manage about my clothes, your honour; I left them at the place where I've been lodging?

Mr. Wilmot: - Oh, I've nothing to do with your clothes. The parties then retired.

Source: The Britannia and Trades' Advocate (Hobart Town, Tas. : 1846 - 1851) Mon 20 Jan 1851 Page 3 Police. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/225557365

H.M.S. "Havannah" at Hobart, VDL

The frigate's arrival in the Derwent on 26th December, 1850, and the landing of Major-General Wynyard was heralded by a salute from the vessel and the battery, witnessed by a crowd which no doubt included the intended deserter of the

Rattler, one Mr. Henry Geeves.

TRANSCRIPT

THE HAVANNAH. - H.M.S.Havannah, having on board Major-General Wynyard, who is on a visit of inspection, arrived yesterday from Sydney. The appearance of the vessel entering our noble harbour, with royals and studding-sails set, and a gentle sea breeze making the waters of the Derwent to dance and glitter in the sunlight, was beautiful. At three o'clock the Major-General landed under a salute from the vessel and the battery. He was waited upon by his Excellency's Aide-de-Camp and a guard of honor, and immediately proceeded to Government house on horse back. A large concourse of people gathered together to witness his landing.

Source: THE HAVANNAH Colonial Times Fri 27 Dec 1850 Page 2 Local Intelligence

The following evening, a grand ball was held at the Military Barracks in Davey Street for the officers of the

Havannah, including the wife and daughter of Major-General Wynyard. Dancing was "

kept up until 4 o'clock in the morning":

Hobart Courier, 27 December 1850

Hobart Courier, 27 December 1850

Ball at the Military Barracks, Hobart for officers of HMS Havannah

TRANSCRIPT

BALL AT THE MILITARY BARRACKS.- Lieut. Colonel Despard and the Officers of the 99th Regiment, gave a grand ball at the Military Barracks on the 14th instant. His Excellency the Lieutenant Governor, the Commander of the Forces, Lady Denison, Mrs and Miss Wynyard and suite, the Officers of the Havannah, and a large company comprising nearly all the beauty, fashion and intelligence of Hobart Town were present. The dancing was kept up until 4 o'clock in the morning. The refreshments were provided by Sergeant Cleary, on whom they reflected infinite credit.

Another frigate, HMS

Meander - sometimes written as HMS

Maeander also visited Hobart in 1850; one its officers, Josiah Thompson, found himself the object of

diarist and socialite Annie Baxter's affections.

H.M.S.

Maeander 44 Guns, in a Heavy Squall (Pacific July 9th 1850)

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Object ID PAH0902

Description Hand-coloured. This print depicts the HMS ‘Meander’, a 44-gun 5th rate frigate. She is sailing in a heavy squall or storm in the Pacific, and is depicted listing dangerously to port with her sails billowing and in chaos. The ship is shown dramatically as being on the verge of being lost at sea, but for the skill and determination of her crew. This is said in the inscription, which also dramatizes the orders given to the men aboard in such a situation. The painting dramatizes an actual situation the ship was in on July 9th, 1850.

Date made 13 Dec 1851

Artist/Maker Dutton, Thomas Goldsworthy

Rudolph Ackermann

Credit National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Materials lithograph, coloured

Measurements Sheet: 381 x 551 mm; Mount: 18 15/16 in x 25 in

Parts H.M.S. Maeander 44 Guns, in a Heavy Squall (Pacific July 9th 1850) (PAH0902)

H.M.S.

Meander 44 guns shortening sail for anchoring (Rio, June 9th 1851)

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Object ID PAH0898

Description Hand-coloured. This print depicts the HMS ‘Meander’, a 44-gun 5th rate frigate. She is shown anchoring in the port of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, shortening her sails in preparation – an actual scene on June 9th, 1851. A view of the port of Rio is shown in the general background, which includes buildings and the city skyline as well as other docked vessels. Among the other vessels depicted is a two-masted paddle steamer, directly to the right of ‘Meander’ in the background. Also on the right is a small two-masted sailing boat in the foreground. Another small boat can be seen close to the stern of the subject ship.

Date made 1 Jan 1852

Artist/Maker Dutton, Thomas Goldsworthy

Rudolph Ackermann

Credit National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Materials lithograph, coloured

Measurements Sheet: 371 x 461 mm; Mount: 480 mm x 631 mm

Parts H.M.S. Meander 44 guns shortening sail for anchoring (Rio, June 9th 1851 (PAH0898)

Francis Guillemard Simpkinson de Wesselow,(1819–1906), naval officer, artist and nephew of Sir John Franklin, arrived in Hobart, VDL on the

Pestonjee Bomanjee in 1844 and departed in 1849 on the

Calcutta. He devised this panorama of Hobart Town in 1848 as a watercolour viewed from the Ross Bank Magnetic Observatory where he worked and lived. In 1900 he wrote from London to the Bishop of Tasmania:

I happen to have several volumes of drawings and sketches made during the years I passed there – 1844 to 1849 – which have been lying packed away almost ever since my return. I am exceedingly glad there is now a chance of their being of some use or interest, I forward them to you with much pleasure.

Hobart Town in 1848 (detail), 1848, F G Simpkinson (de Wesselow), pencil, watercolour and chinese white on six sheets.

Royal Society of Tasmania Exhibition 2019, TMAG. Link: https://rst.org.au/francis-simpkinson-de-wesselow/

Hobart Town in 1848 (detail), 1848, F G Simpkinson (de Wesselow), pencil, watercolour and chinese white on six sheets.

Royal Society of Tasmania Exhibition 2019, TMAG. Link: https://rst.org.au/francis-simpkinson-de-wesselow/

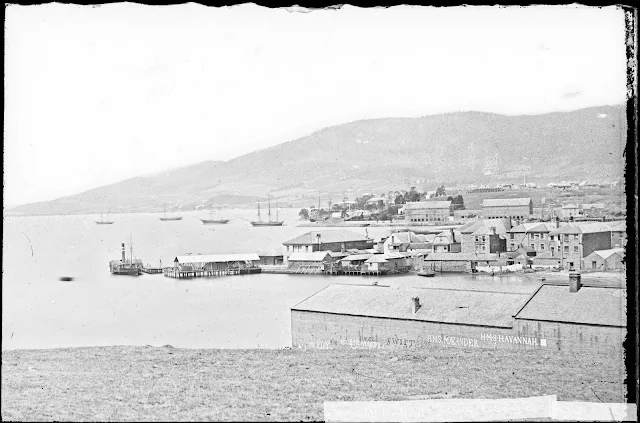

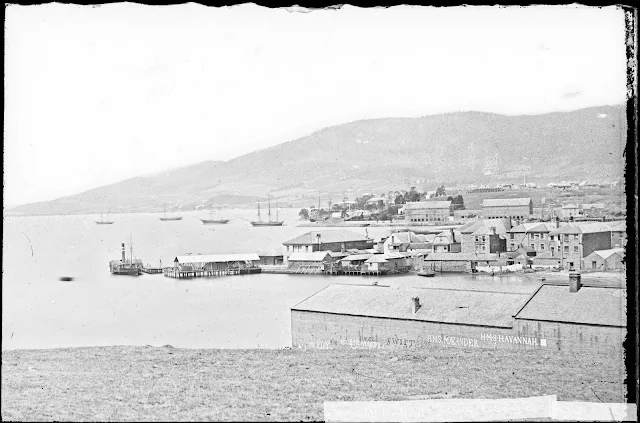

Simpkinson de Wesselow captured the scene above in 1848. The photograph (below) undated, unattributed and printed from a glass negative, captured the same scene with the addition of the names painted on the side of the sheds which were allocated to the naval frigates HMS

Havannah and HMS

Meander in 1850 at the time of their visit. If the photograph was taken in 1850-51, the ship closest to the Battery at Secheron Bay would therefore be HMS

Havannah and the steamer moored at the Regatta Point jetty would most likely be the government's PS

Kangaroo, sold out of public service in July 1851.

HMS Meander and HMS Havannah, ship's names on shed, Hobart

Undated, unattributed, print from glass negative

Archives Office Tasmania Ref: NS1013-1-991

HMS Meander and HMS Havannah, ship's names on shed, Hobart

Undated, unattributed, print from glass negative

Archives Office Tasmania Ref: NS1013-1-991

This panorama taken by John Sharp in 1857 shows HMS Meander and HMS Havannah, the ship's names on shed in the foreground of the image on extreme left, but details in the distance of the jetty, if it was there, are indiscernible.

8. Hobart from the Domain (panorama) / Sharp photo ca. 1857

Archives Office Tasmania

https://stors.tas.gov.au/ABBOTTALBUM$init=ABBOTTALBUM_AUTAS001136186327

8. Hobart from the Domain (panorama) / Sharp photo ca. 1857

Archives Office Tasmania

https://stors.tas.gov.au/ABBOTTALBUM$init=ABBOTTALBUM_AUTAS001136186327

The cattle jetty and walkway, which was not yet built in 1848 when Simpkinson de Wesselow painted the scene, appears clearly in the black and white print from a glass negative (above) taken in the 1850s, but when commercial photographer Thomas J. Nevin photographed the same scene in the 1860s, the cattle jetty was no longer there. He devised this hand-coloured stereograph of the cattleyards and abbatoir, now located on the foreshore directly below the boat sheds.

Stereograph on arched buff mount of the Abbatoir, Queen's Domain, Hobart

Photographer; Thomas J. Nevin late 1860s for the HCC, Lands and Survey Dept

Unstamped, and hand-coloured

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Collection

TMAG Ref: Q1994.56.25

State of the Colony 1850-1851

Stereograph on arched buff mount of the Abbatoir, Queen's Domain, Hobart

Photographer; Thomas J. Nevin late 1860s for the HCC, Lands and Survey Dept

Unstamped, and hand-coloured

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Collection

TMAG Ref: Q1994.56.25

State of the Colony 1850-1851

Below is an extended extract from Godfrey Charles

Mundy's publication

Our Antipodes or, Residence and Rambles in the Australasian Colonies, with a Glimpse of the Goldfields (London, Richard Bentley 1852). The illustrations are from the third edition published in 1854.

Deputy adjutant general Godfrey Charles Mundy arrived at Hobart on board HMS

Havannah with Major-General Wynyard on 26th December, 1850. His lively observations by way of the short history of the colony are remarkably accurate and familiar in tenor, even today. The account (below) of his experiences in Tasmania begins on 23rd December 1850 and ends on January 18th, 1851, when he departed for Port Phillip, Victoria. He would have made the acquaintance of Captain Edward Goldsmith during a very busy festive season, if

Annie Baxter's diary is any indication, and he would have learnt that the small paddle steamer PS

Kangaroo (52 tons, ex the Sydney-Parramatta river service) which was placed at his disposal by Lieut.-Governor Denison for the overnight trip down the Derwent estuary to the Iron Pot, Betsy's Island, Slopen Island and Norfolk Bay would be decommissioned and sold in July 1851. It would be replaced by Captain Goldsmith's larger vehicular twin steam ferry SS

Kangaroo, funded in part by an Act legislated in July 1850 to subsidize a loan from Treasury of £5000 with interest. Captain Goldsmith's twin ferry SS

Kangaroo was launched eventually in 1854, after severe personal, financial and political setbacks.

Paddle steamer PS Kangaroo ca. 1850

National Library of Australia nla.obj-147501557-1.jpg

Paddle steamer PS Kangaroo ca. 1850

National Library of Australia nla.obj-147501557-1.jpg

BIOGRAPHY: Godfrey Charles MUNDY (1804-1860)

Godfrey Charles Mundy (1804-1860), soldier and author, was born on 10 March 1804, the eldest son of Major-General Godfrey Basil Mundy and Sarah Brydges, née Rodney, daughter of the first baron Rodney (1718-1792) who defeated the French Fleet under Comte de Grasse off Dominica in 1782.

Mundy entered the army as an ensign in 1821, was commissioned lieutenant in 1823, captain 1826, major 1839, lieutenant-colonel 1845, and colonel 1854. In 1825-26 he was decorated while serving in India as aide-de-camp to Lord Combermere at the siege and storming of Bhurtpore. He was later stationed in Canada and arrived in Sydney from London in the Agincourt in June 1846 as deputy adjutant general of the military forces in Australia. He left in August 1851 and during the Crimean war was appointed under-secretary in the War Office. On 4 April 1857 he was appointed lieutenant-governor of Jersey in the Channel Islands with the local rank of major-general. He died in London on 10 July 1860 survived by his wife Louisa Katrina Herbert, whom he had married in Sydney on 6 June 1848, and by their son.

In 1832 Mundy published Pen and Pencil Sketches, Being the Journal of a Tour in India, and in 1852 Our Antipodes: or, Residence and Rambles in the Australasian Colonies. With a Glimpse of the Gold Fields. He illustrated Our Antipodes with landscapes and lively scenes engraved from his own sketches. The first book went through three editions and the second four, not counting translations in German (1856) and Swedish (1857).

In Australia Mundy accompanied his cousin Governor Sir Charles FitzRoy on several outback tours in New South Wales, and he visited Victoria, Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand. Aristocratic by birth and conventional in temper, he showed in his books a discerning eye, a lively pen, a keen sense of humour and a marked streak of sturdy common sense. Our Antipodes still makes entertaining reading and is an invaluable source of information for the Australian social historian. To read the book is to like the author.

Source: Australian Dictionary of Biograph (Ken Macnab and Russel Ward 1967)

Third edition cover of Godfrey Charles Mundy's publication, Our Antipodes or, Residence and Rambles in the Australasian Colonies, with a Glimpse of the Goldfields

Author: Mundy, Godfrey Charles (1804-1860)

Published at London, by Richard Bentley 1852-1854

Extracts from the 1852 edition

Third edition cover of Godfrey Charles Mundy's publication, Our Antipodes or, Residence and Rambles in the Australasian Colonies, with a Glimpse of the Goldfields

Author: Mundy, Godfrey Charles (1804-1860)

Published at London, by Richard Bentley 1852-1854

Extracts from the 1852 edition

"Chapter V. [1850–51.]

EXCURSION TO THE COLONIES OF VAN

DIEMEN'S LAND AND VICTORIA — VOYAGE

— MARIA ISLAND — MORTIFYING

RECEPTION — MR. SMITH O'BRIEN — OUTREASONED AND OUT-MANOEUVRED — THREE

GENERATIONS EXPATRIATED — CHRISTMAS

TIDE IN FAR LANDS — A MAN OVERBOARD

— HOBART TOWN — GARDENS AND VILLAS

— ICE — THE METROPOLITAN COOK

— MASTERS OF ARTS — CONVICTS — THEIR

LABOUR — A COUNTRY WITHOUT AN

HISTORIAN — FIRST SETTLEMENT — A BATTUE

FOR BLACKS — THEIR REMNANT.

IN the Australian summer of 1850–51, the chances of the service threw

in my way an agreeable opportunity of visiting Van Diemen's Land, as

well as Port Phillip, a province of New South Wales on the point of

being erected into a colony under the title of Victoria. Major General

Wynyard, commanding the forces in the Australasian colonies, having

resolved on a tour of inspection to the former island, I had the honour to

accompany him on that duty.

The elements did not favour

H.M.S. Havannah, which frigate

conveyed us to our destination, for she commenced her voyage with a

terrific thunder-storm, in which the electric fluid flirted most desperately

with the conductor on the main-mast, and during the rest of the voyage

she had calms and adverse winds to contest with, so that no less than

eleven days were expended in performing the 600 miles between Sydney

and Hobart Town. But if the southerly breeze resisted our progress, its

fresh breath proved a charming relief to us, after the heat of Sydney. A

day or two before we left that (at this season) sudoriferous city, the

thermometer stood at 97° and 98°, yet at sea we enjoyed the bracing

effects of a temperature from 50° to 48° between decks; — enjoyed, I can

hardly say, for to most of us this degree of cold seemed well-nigh

inclement. On the

23d December, harassed by continued foul winds,

Captain Erskine closed in with the land to seek an anchorage, and we

soon found ourselves surrounded on the chart by names commemorative

of the old French surveyors and discoverers. Leaving behind us

Freycinet's Peninsula, and beating to and fro between the storm-lashed

Isle des Phoques and Cape Bougainville on the mainland of Van

Diemen's Land, we at length gained a snug berth off the settlement of

Darlington on Maria Island, about a mile and a half from the shore, and

half that distance from L'Isle du Nord.

December 24th. — The wind continuing both foul and fresh,

Havannah remained at anchor during the morning; and landing after

breakfast, we seized by the forelock this unlooked-for opportunity of

visiting the island and its chief town. Singular enough! in one of the

latest numbers of the

Illustrated London News on board was found a

short account of Maria Island, with a woodcut of the settlement, which

had become interesting as the prison of Mr. Smith O'Brien.

The island is about twenty miles long, and is separated from the

mainland by a channel varying from four to eight miles in breadth. The

land is elevated and covered with wood. Maria Island derives its

feminine appellation from Miss Van Diemen, whose charms appear to

have so deeply impressed the heart of her compatriot the great navigator,

Abel Tasman, that in his oceanic wanderings, not finding it convenient

“to carve her name on every tree,” he recorded it still more immortally

on different headlands and islands newly discovered, — inscribing it, in

its full maiden length, on the northern-most bluff of New Zealand, Cape

Maria Van Diemen. Whether he assisted the fair lady to change it

eventually, I cannot depose.

In 1825 this island was made a penal settlement for convicts whose

crimes were not of an aggravated nature, — a purpose for which it is

admirably adapted by its isolated position and its ready communication,

by telegraph or otherwise, with Hobart Town. The establishment was

broken up in 1832, and the land was rented to settlers; but it was resumed

when the Probation System was introduced, and has since again been

vacated as a Government station.

The soil is fertile. About 400 acres have been cleared round

Darlington; and the crops in both field and garden have been most

plentiful. Forty bushels of wheat per acre is accounted a high average in

any of the Australian colonies; and that average is common here. The

timber is magnificent, but so much has been already taken that the larger

blue-gums and iron-barks must now be sought in the distant gulleys of

the mountains. The largest I saw was about eighteen feet in girth, — a

slim-waisted sprig in Tasmanian estimation. There are many rivulets and

lagoons of excellent water on the island, — an advantage by no means

generally conspicuous in Van Diemen's Land. There is plenty of fish,

eels and oysters, quail and wild fowl, as well as wallabi, — a small kind

of kangaroo. The climate is about the finest in the world, — a fact

admitted by Smith O'Brien himself, who, among all his Jeremiads indited

from Maria Island, could not resist doing justice to the picturesque

beauty and the salubrity of his place of exile.

Aware that Darlington had been a Probation Station containing some

four hundred prisoners, and unapprised of its abandonment; and,

moreover, giving our ship and ourselves credit for being a sight worth

seeing and seldom seen by the supposed inhabitants, good and bad, bond

and free; we were not a little surprised — perhaps the captain was a little

nettled — at perceiving in the settlement no commotion arising from the

advent of

H.M.S. Havannah. The tall flag-staff was buntingless, the

windmill sailless, the pretty cottages and gardens seemed tenantless, “not

a drum was heard” in the military barracks, and the huge convict

buildings seemed to be minus convicts. At length, through a telescope,

was observed one canary-coloured biped, in the grey and yellow livery of

the doubly and trebly-convicted felon. There had perhaps been an

outbreak of the prisoners, for the military force in Tasmania had lately

been reduced to the very lowest possible amount! The magistrates,

superintendents, overseers, officers, and soldiers had all been massacred;

and the revolted convicts having afterwards fought about the spoil,

— there stood the sole survivor! Our suspense did not last long, for

presently a whale-boat came slowly off, and there appeared on the

quarter-deck, a hawk-eyed and nosed personage, about six feet and a-half

high, who seemed as if he had long lived in indifferent society, for his

eyes had a habit of sweeping around his person, aside and behind, as

though he was in momentary expectation of assault. This was an overseer

left in charge of the abandoned station, with a few prisoners to assist

him. He proved an obliging and intelligent cicerone, showing our party

over the different buildings of the establishment, and guiding us in a

delightful walk over part of the island. The position of Darlington is truly

delightful — airy, yet sheltered, with a splendid view of the open ocean,

of the straits, and of the fine blue hills and wooded bluffs of the

mainland. A clear stream of fresh water meanders among the houses, and

loses itself in a snug little boat harbour.

Pity that, as in Norfolk Island, a paradise should have been converted

into a pandemonium; and yet again it seems a pity that so extensive and

expensive an establishment — hospital, stores, chapel, school, military

and convict barracks, houses of the magistrate, surgeon, superintendent,

&c. — should be abandoned to ruin. It would be more satisfactory to see

them all swept out of sight — obliterated from the soil — and this lovely

isle allotted to a population worthy of its numerous advantages. There

was one feature of this defunct convict station that I viewed with

disgust — a single dormitory for four hundred men! The bed places were

built of wood in three tiers, the upper cribs being reached by two or three

brackets fastened to the stanchions. Each pigeon-hole is six feet and a

half long, by two feet in width, and separated from its neighbours by

double, open battens. The prisoner lies with his feet to the outer wall and

his head towards the centre of the apartment — like a bottle in its bin.

This nocturnal aggregation of brutalized males is a feature of penal

discipline that I was astonished to find had been so lately in operation.

The accommodations allotted to Mr. William Smith O'Brien, the state

prisoner, were of course pointed out to us. They consisted of two small

rooms, with a little garden in the rear, wherein he might take his exercise.

Few field-officers of the army obtain better quarters, and many worse.

He was waited upon by a constable, who cooked his convict ration of

beef, bread, and potatoes, and, I suppose, made his “post and rail” tea

sweetened with brown sugar. The prisoner was as poor a philosopher as a

patriot. He had not courage to reap what he had sown. He refused, as is

well known, to accept the ticket of leave offered him by Government,

and yet winced under the consequent and necessary hardships incurred

by this refusal.

A medical gentleman, whose duty it is to visit periodically all the

convict stations, related to me a curious interview he had with this

political delinquent. On announcing his desire to see Mr. O'Brien, he was

politely received by that person, and conversed for some time with him.

The prisoner complained of his rations, of the coarse tea and sugar, said

his health suffered from the bad food, and from confinement to the small

strip of garden. The doctor, who is not a man readily put off his guard,

admitted that it was not impossible that the long continuance of an

existence of privation and humiliation might indeed affect injuriously

both mind and body; and added that he should be happy to do anything in

his power to alleviate his sufferings. O'Brien was glad to hear such

sentiments from his visitor, and expressed a hope that he would apply to

the Governor to sanction some relaxation of discipline. The doctor,

pointing to two prisoners in the yard, said — “If the health of those men

was, in my opinion, injured by their imprisonment and punishment, I

should represent their cases, because they cannot help themselves. You,

Sir, on the contrary, have your health and comfort in your own hands;

— one word, and you may live as you please on this island.” The poor,

vain, egotist, replied that he must be consistent, that the eyes of the world

were upon him, that the acceptation of his ticket-of-leave would amount

to an admission of the justice of his sentence. “But you speak, Sir,”

added he, “as if I had committed a crime! What crime have I

committed?” “A monstrous one,” replied the good Medico — “you have

broken the laws of your country, and stirred up your ignorant fellow

countrymen to break them also.” He moreover assured the prisoner that

Europe was in no disquiet as to his fate. The latter, however, remained

obdurate on the subject of his ticket — preferring to retain his grievance

with the accompanying possibility of escape. The miserable attempt

which he shortly afterwards made will not add to his character for

ingenuity or fortitude. A cutter appeared in the bay. Smith O'Brien, duly

warned of its approach, contrived to procure a small boat, and was in the

act of pushing off, when a single, armed constable, came up and stove

the boat with a blow of an axe, while a whale-boat, well armed, pulled

away and captured the cutter.

The “Inspector General of the Confederated Clubs of Munster,” and the

descendant of Brian Boru, behaved on this occasion like a petulant child.

He ran into the sea some paces, and, when compelled to re-land, refused

to walk, and, having thrown himself down on the ground, suffered

himself to be carried like a sack back to his cell by three or four men;

— a mode of bearing reverses by no means heroical. The fact of a

ticket-of-leave having been accorded to this troublesome gentleman not long

after this effort at evasion, is proof enough of clemency on the part of

Government; yet while he was enjoying himself in almost perfect

liberty — in liberty as perfect as that within the reach of any professional

man, whose duties bind him to one district — a letter, addressed to “My

dear Potter,” was running the round of the English papers, wherein he

descants on “the inhumanity of the Governor of the colony,” and on “the

inhuman regulations of the Controller-General of Convicts”

— concluding by the doleful prophecy, “I see no definite termination of

the calamities of my lot, except that which you and other friends took so

much pains to avert — the deliverance which will be effected by death.

”18

The English are, indeed, wonderful curiosity-mongers, especially in

matters connected with crime and criminals. A Nineveh of relics

appertaining to murders and murderers would find scores of Layards to

grub them up and set store by them. Pieces of blue crockery on which the

convicted traitor was supposed to have dined, shreds of the scuttled boat

in which he hoped to have fled from his South Sea Chillon, with other

trivial mementos of the kind, found their way on board the frigate. But in

this trumpery reliquiarium I read only a sly mockery of that vulgar

mistake, pseudo-dilettanteism.

It was really melancholy to see the beautiful gardens around the houses

of the departed officers of the penal station, “wasting their sweetness on

the desert air,” and reverting to the original wilderness. On this day,

however, the luxuriant flowers did not bloom in vain; for the sailors,

pillaging the gardens of the deserted villas, carried off to the ship whole

arm-fulls of their produce to decorate the tables for their Christmas

dinner on the morrow. And indeed never, I suppose, did the 'tween-decks

of a man-of-war resemble half so much —

“A bower of roses by Bendemeer's stream,”

as did, on this festive occasion, that of

H.M.S. Havannah, off a ruined

convict station on a wild island of Tasmania.

Our tall overseer welcomed us to his house, or rather to that of the

absent superintendent, which he was permitted to occupy, and gave those

of the party who had not lately been in Europe a real treat by turning us

loose into an acre of gooseberry and raspberry bushes, fruits unknown in

New South Wales. The family consisted of three generations, the

overseer's half-dozen children being perfect models of bloom — bloom

quite as rare in New South Wales as the English berries above

mentioned. The eldest generation was represented by a tall, stout, and

dignified matron, with whom I had a long and pleasant talk about old

England. In the course of the domestic revelations I elicited from this

truly venerable lady, she now and then startled me by the expression

— “Our connexion with royalty” — which seemed to weave itself

unconsciously into the web of her discourse, and which jarred somewhat

discordantly with the comfortless state of their abode. For want of a

clew, my imagination took the liberty to follow up a fancied resemblance

to the Guelph lineaments in the comely profile of the portly dame before

me; and I was glancing towards two well-painted kit-cats — one

representing a gentleman in powder, frill, blue coat, and buff vest; the

other a boy in light blue tunic, hat, feather, and dog — and I was running

“full cry” on the trail of my theory, when she at once “whipped me off,”

by informing me that the first was her deceased husband, who was

“page” to his Majesty George the — — to the day of his death; the latter

her son, the overseer. Poor people! It was clear they had seen better days.

Having passed a very pleasant and a very beautiful day on Maria

Island, we repaired on board at 6 P.M., up anchored, sailed, dined, and

slept, rocked by old Neptune, our marine cradle making bows to every

point of the compass as she rode on the swell left by the departed

southern gale, during a breathless night.

Christmas Day. — Our hopes of participating at Hobart Town in the

joyful rites of the day were frustrated; for the light north-east airs that

arose in the forenoon, carried us no further than Cape Pillar and Tasman

Island — the former the extreme salient angle, the latter the uttermost

outwork of Van Diemen's Land towards the boundless ocean of the

south. I have passed this great festival of the Christian world in many

diverse scenes and under diverse circumstances. Amid the old-fashioned

hospitality and the ice and snow of old South Wales; in the Antipodal

sultriness of New South Wales — (Nova Cambria, she should be styled;)

I have joined in the service of the day on the brink of the Falls of

Niagara — the drum-head, the reading desk, in the centre of a square of

infantry — the thunder of the great cataract hymning in sublime diapason

the omnipotence of God. I have eaten my Christmas dinner at the

presbytère of a French Roman Catholic establishment — not the less

jovially because the mess was composed of a grand vicaire and a score

of prêtres and frères. I have passed the evening of this anniversary with a

knot of Mussulman chiefs, gravely smoking our hookahs and sipping

sherbet, while a group of Nautch girls danced and sang before us; have

stood with uncovered head at the foot of one of New Zealand's

volcanos — the fern our carpet, the sky our canopy — listening with a

congregation of baptized Maoris to a tattooed teacher expounding in their

own tongue the law of Christ on the anniversary of His birth. How

seldom since boyhood have I celebrated it in the happy circle of my own

quiet home! It was certainly never pre-revealed to me that I should spend

one of the few Christmas days accorded to man, at sea off the

southermost point of Van Diemen's Land!

The crew of the frigate, as I have said, decorated their feast of roast

beef and plum-pudding on this occasion with the ravished sweets of

Maria Island. It was a singular and pleasant sight, passing down the

various messes, to see the hungry, happy and hearty faces grinning

through the steam of their holiday viands, and through garlands of gay

coloured flowers and shrubs, lighted up with wax candles. The captain's

table was not without its épergne, the ladies without bouquets, (for Mrs.

and Miss Wynyard were of the party,) nor the gentlemen without a

flower at their button-holes on this South Sea Christmas evening.

Cape Pillar and Tasman Island, close to which we passed, have a

singular appearance, their southern extremities terminating in abrupt

basaltic walls, whose tall upright columns bear a resemblance to the

pipes of a huge cathedral organ. My sketch, wholly unworthy of so fine a

subject, was taken through the porthole of my berth — a long thirty-two

pounder disputing with me the somewhat circumscribed view.19

December 26th. — At early dawn we were rounding Cape Raoul, a

twin of Cape Pillar; and the sea breeze setting in soon carried us up the

river Derwent, or rather the magnificent arm of the sea and harbour into

which that stream empties itself, and on the extreme north-western

corner of which stands the city of Hobart Town.

With studding-sails set alow and aloft the

Havannah — like a swan

swimming before the wind — glided past the Iron Pot lighthouse and

between high and wooded shores, the splendid harbour gradually

narrowing from seven or eight miles to one or two, until, at about

eighteen miles from the Heads, she rounded a bluff promontory on the

port side, and in an instant dashed into the midst of a little fleet of

merchant vessels, in the snug inlet called Sulliven's Cove. The chain

cable rattled out of the hawseholes in a volume of rusty dust, and the old

ship swinging to her anchor brought up with her cabin windows looking,

at no great distance, into those of Government-house. There was but one

momentary interruption to her stately approach as observed from the

shore; her feathers fluttered for an instant and were almost as quickly

smoothed again. In relieving the man at the lead line, one of them fell

overboard; the ship was thrown up into the wind so as to check her speed

almost before the splash was heard; the young fellow held on to the line

and was dragged for some distance under water; but he was soon noosed

by his ready messmates, and spluttering out “all right,” was jerked on to

the quarter-deck like a two-pound trout, none the worse for his ducking.

“Did you think of the sharks, Bo?” asked a joker as he helped him down

the hatch-way to be “overhauled” by the doctor. “Hadn't time,” gasped

the other.

The harbour of Hobart Town is as commodious and safe as it is

picturesque. The well-worn expression that all the navies in the world

might ride in it would not be extravagantly applied to it. I am loth to

yield my predilection for Sydney harbour which is quite unique in my

eyes; but nautical men seem, I think, to prefer the Derwent. There is

more space for beating, and no shoal like the “Sow and Pigs” lying

across its jaws.

The land in which the port is framed is three times higher than that of

Port Jackson, the soil better, the timber finer, and the grand back-ground

to the town afforded by Mount Wellington — cloud-capped in summer,

snow-capped in winter — close in its rear, gives the palm of picturesque

beauty, beyond dispute, to Hobart Town and its harbour over its sister

port and city. The land-tints disappointed me entirely — nothing but

browns and yellows — no verdure — everything burnt up, except where

an occasional patch of unripe grain lay like a green kerchief spread to dry

on the scorched slopes.

The water frontage of the city does not afford a tenth part of the deepwater

wharfage possessed by Sydney. The site of the town is healthy,

well adapted for drainage, perhaps somewhat too near the storm-brewing

gulleys of the mountain, from whence occasional gusts sweep down the

streets with a suddenness and severity very trying to phthisical subjects.

The population may be about 20,000, convicts included, or

considerably more than one-fourth of the whole population of the colony.

The streets are wide and well laid out, nearly as dusty, and the footpaths

as ill paved as those of Sydney, which latter defect, with so much convict

power at hand, is disgraceful enough.

Some of the suburbs are very pretty, the style of architecture of the

villas, their shady seclusion, and the trimness of their approaches and

pleasure-grounds far surpassing those of the New South Wales capital.

But more pleasing to my eyes, because more uncommon than the

ordinary domiciliary snugness and smugness of the villas of the richer

English, was a large quarter outskirting the town, consisting of some

hundreds of cottages for the humbler classes, pleasantly situated on the

slope of a hill, all or nearly all being separate dwellings, with a patch of

neat garden attached, and with rose and vine-clad porches, reminding one

of the South of England cotters' homes.

The extraordinary luxuriance of the common red geranium at this

season makes every spot look gay; at the distance of miles the sight is

attracted and dazzled by the wide patches of scarlet dotted over the

landscape. The hedges of sweet-brier, both in the town-gardens and

country-enclosures, covered with its delicate rose, absolutely monopolize

the air as a vehicle for its peculiar perfume: — the closely-clipped mint

borders supplying the place of box, sometimes, however, overpower the

sweet-brier, and every other scent of the gardens.

Every kind of English flower and fruit appears to benefit by

transportation to Van Diemen's Land. Well-remembered shrubs and

plants, to which the heat of Australia is fatal, thrive in the utmost

luxuriance under this more southern climate. For five years I had lost

sight of a rough but respected old friend — the holly, or at most I had

contemplated with chastened affection one wretched little specimen in

the Sydney Botanic Garden — labelled for the enlightenment of the

Cornstalks. But in a Hobart Town garden I suddenly found myself in the

presence of a full-grown holly, twenty feet high and spangled with red

berries, into whose embrace I incontinently rushed, to the astonishment

of a large party of the Brave and the Fair, as well as to that of my most

prominent feature!

The fuchsia, the old original Fuchsia gracilis, attains here an

extraordinary growth. Edging the beds of a fine garden near where I

lived, there were hundreds of yards of fuchsia in bloom; and in the

middle of the town I saw one day a young just-married military couple

smiling, in all the plenitude of honey-lunacy, through a cottage-window

wholly surrounded by this pretty plant, which not only covered the entire

front of the modest residence, but reached above its eaves. And this

incident forces on my mind a grievous consideration, however out of

place here, namely, the virulent matrimonial epidemic raging lately

among the junior branches of the army in this colony. “Deus pascit

corvos,” the motto of a family of my acquaintance, conveys a soothing

assurance to those determined on a rash but pleasant step. But who will

feed half-a-dozen raven-ous brats is a question that only occurs when too

late! At this moment the regimental mess at Hobart Town is a desert

peopled by one or two resolute old bachelors and younger ones clever at

slipping out of nooses, or possessing that desultory devotion to the sex

which is necessary to keep the soldier single and efficient. Punch's

laconic advice “to parties about to marry,” which I have previously

adverted to, ought to be inserted in the standing orders and mess rules of

every regiment in H.M.'s service.

Here, too, to get back to my botany, I renewed my acquaintance with

the walnut and the filbert, just now ripe, the Spanish and horse-chestnuts,

the lime-tree with its bee-beloved blossom, and the dear old hawthorn of

my native land. As for cherry and apple-trees, and the various

domesticated berry-bushes of the English garden, my regard for them

was expressed in a less sentimental manner. I defy schoolboy or

“midship-mite” to have outdone me in devotion to their products,

however much these more youthful votaries may have beaten me in the

digestion of them.

From the grounds of the hospitable friend who made his house my

home during the fortnight I stayed at Hobart Town, the landscape was

extremely beautiful and much more European than Australian in its

character. Looking over villas and gardens and wooded undulations, with

glimpses of the town through vistas of high trees, down upon the bright

waters of the wide and hill-encircled harbour, I recalled to mind various

kindred prospects in older countries, — none more like than a certain

peep from a campagne near Lausanne over the village of Ouchi upon the

broad expanse of “clear, placid Leman.” Behind the house, Mount

Wellington, step by step, rises to the height of four thousand feet and

upwards, throwing its grand shadow, as the sun declines, right across the

city and harbour. Bristling with fine trees and brushwood, this range,

which can never be cultivated, will always supply the town with fuel and

timber for building.

If no other public act of the present Governor may gain him

immortality, — which I am far from supposing, — the plan and

establishment of an ice-house near the summit of the mountain will serve

that purpose. It is the only one at the Antipodes. During the winter the

“diadem of snow” which crowns the top is pilfered to a trifling degree,

and the material well jammed into the ice-house. In the hot weather a

daily supply is brought into town on a pack-horse — (it ought to be done

by a self-acting tram-way) — early in the morning, and its sale and

manufacture is permitted by general consent to be monopolized by the

chief confectioner of the place, who sells it in the rough or in the smooth,

reasonably enough, to those who can afford ice creams, hard butter, and

cool champagne. This now respectable tradesman and citizen, once a

prisoner of the Crown, enjoys, moreover, another important and lucrative

monopoly. He is the cook as well as pastrycook of the Hobarton

aristocracy, — the only cook in the place. I sat at not a few “good men's

feasts” during my short stay here, and am not wrong, I think, in saying

that from the Government-house table downwards, all were covered with

productions of the same artiste. I recognised everywhere the soups, the

patés; I ventured upon this entremêt, avoided that, with the certainty of

prior knowledge; plunged without the shade of a doubt into the recesses

of a certain ubiquitous vol-au-vent, perfectly satisfied that a vein of

truffles would be found, which had not crossed 16,000 miles of ocean to

be left uneaten, although their merits seemed to be unknown to some.

The cook, it is needless to say, is making, if he has not already made, a

considerable fortune.

It were well if those professions which administer merely to the body

had alone fallen into the hands of persons bearing upon them the convict

taint; — the reverse is, however, the case. What would an English

mother think of admitting to her drawing-room or school-room, and

entrusting the education of her daughter in music, dancing, or painting, to

men who are or have been felons? Yet at present this is almost a

necessity in Van Diemen's Land. Few or no accomplished freemen are

likely to come to a penal colony in the hope of making a livelihood by

imparting the more elegant branches of education. They are wrong,

however, for if their expectations were moderate such men might realize

handsome incomes.

A lady told me that she had been compelled to employ, for the purpose

of teaching, or taking the portrait of her daughter — I forget which — a

person convicted of manslaughter, and suspected of murder by

poisoning. One of her sons usually remained in the room when this

agreeable guest was present; but, on one occasion when the ladies

happened to be alone with him, the mother was alarmed by seeing him

rise and approach the window where she sat, with an open knife in his

hand. She started from her chair with such visible affright, that, making

her a polite bow and with a grim smile, he begged to assure that “he

merely wanted to cut his pencil — not her throat!”

I had the honour of being a fellow-traveller and dining several times at

a public table with a transported professor of one of those lighter

sciences usually inflicted upon young ladies, whether or not they have

any natural talent for them. What was the immediate cause of his exile

from home my neighbour and informant could not tell me, “but I believe

it was the gentleman's crime — forgery,” said he. Be it as it may, this

“gentleman” was in excellent and full practice, although in this

hemisphere, it was said, he had repaid the indulgence of the Government

and the confidence of one of his most respectable patrons, as well as one

of the kindest friends the convict class ever possessed, by debauching the

child entrusted to his tuition.

In the streets of Hobart Town the stranger sees less of the penal

features of the place than might be expected. Possibly every other person

he meets on the wharves and thoroughfares may have been transported;

for the population of the island has been thus centesimally divided:

— free immigrants and born in the colony, 46 per cent.; bond and

emerged into freedom, 51 per cent.; military, Aborigines, &c. 3 per cent.

But there is of course no outward distinction of the classes except in the

prisoners under probation, who are clothed in the degraded grey, or grey

and yellow, according to their crimes and character. And these men,

being either confined within walls, or in distant stockades, or being

marched early in the morning to their place of work and back again at

sunset, fall but little under the observation of the public. Now and then

may be seen, indeed, the painful spectacle of a band of silent, soured, and

scowling ruffians — some harnessed to, others pushing at, and another

driving a hand cart, with clanking chains, toiling and sweating in their

thick and dusty woollens along the streets — each marked with his

number and the name of his station in large letters on his back and on his

cap. Here a gang may be seen labouring with shovel and pick on the

roadside, or sitting apart breaking up the metal. There is no earnestness

or cheerfulness in compulsory labour; and accordingly, however active

and ruthless these fellows may have shown themselves in the

commission of violence against their fellow-men, they are most merciful

to the macadam, only throwing a little temporary energy into their action

when the appearance of a carriage or a horseman suggests the possible

advent of some person whose duty or pleasure it may be to keep them up

to their work. As for the convict sub-overseer, who, one of themselves, is

appointed without pay to coerce the rest — no very active control can be

expected from him.

To the colony the amount of solid benefit performed by these slow, but

sure and costless operatives, on the roads, bridges, and other public

works, must have been, and still be, immense; even where, as is

sometimes the case, the settlers of a district have to provide tools and

subsistence for the gangs employed in the improvement of their locality.

It is only this powerful application of penal slave-labour, and the vast

Government expenditure accompanying it, that have given to New South

Wales and Van Diemen's Land a rapidity of progress and a precocity in

importance that leave the march of other colonies comparatively very far

behind.

But to the Mother Country the cost of creating nations by the thews and

sinews of her expelled, but by her still maintained, criminals, must be

enormous. The result of their labour compared with the outlay would be

pitiful indeed, but for the concurrent advantages — namely, the annual

riddance of a huge per-centage of rogues from her shores and from their

old haunts, their punishment and possible reformation, and the creation

of new dependencies of the Crown, and, therein, new markets for

England's exports. The clearing of an acre of land by a chain gang, under

bad surveillance, may cost, and indeed has often cost the Home

Government ten times as much as would have been paid to free labourers

on the spot; but the privilege of shooting so much moral rubbish upon

other and distant premises is cheaply bought at such a rate. It is cheaper

at any rate than a revolution; and it is an old newspaper story that the free

convicts of Paris bore no unimportant part in former as well as the late

overthrow of the Government of France. Van Diemen's Land, however,

like New South Wales, (if one may judge from the exertions made by a

tolerably influential section of the inhabitants,) is striving to shake off the

system, which, incubus though it be, warmed her into life.

Looking at the question from the station of a spectator, I must say it

seems to me rather an unreasonable expectation on the part of those

truant Englishmen, who, well knowing the penal structure of Van

Diemen's Land as a colony, voluntarily settled there, that at the mere

signification of their pleasure the Imperial Government should be

compelled to raze in a moment the great insular penitentiary erected at

such prodigious cost, and hand over its site to the adventurers whose

tastes and consciences have so suddenly become squeamish about

convict-contact. Their grandsons or great-grandsons might, perhaps,

prefer the petition without incurring a charge of presumption; but the

present incumbents have no such claim — unless, indeed, they have

received an imperial pledge to that effect. Like the “Needy Knifegrinder,”

“I do not want to meddle With politics, Sir.”

The colonists know their own business best, and it is none of mine: but

it appears to me that their aspirations are somewhat premature. The

ground-floor of their social edifice has been built of mud. Let it at least

have time to harden before they attempt to superimpose a structure of

marble!

December 30th. — It is curious to find oneself in a country with a

capital containing 20,000 inhabitants, a harbour full of shipping, and

teeming with evidences of wealth and comfort, and yet without a history;

that is, without a manual, a hand-book, or indeed any publication suited

to the reference of a travelling stranger. Mr. Murray must make a long

arm and supply this deficiency. In vain I perambulated the libraries and

stationers — in vain searched the book-shelves of the few residents I was

acquainted with. It was with some difficulty that I obtained the loan of an

old almanack — Ross's almanack — eleven years old. One day, indeed, I

espied in the window of a shop the title, “History of Tasmania,” on the

back of what appeared to be a well got up two-volume octavo work. It

was only the husk, however, the empty cover, no more, of a work that

had not yet seen the light. Subsequently I encountered the author in a

steam-boat, and was by him kindly permitted to look over one of his

well-written and diligently-collated volumes.

Before pressing my reader to accompany me further into the island, I

will, if he pleases, make him a partner in such information as I could

glean regarding earlier events in the history of the colony; whereof,

however, I do not propose troubling him with more than a meagre

summary.

It appears that in 1803, fifteen years after the first settlement of New

South Wales, to which place some 6,000 or 7,000 persons had been

transported, and which had suffered under the horrors of famine,

insurrection, and other troubles, it was found desirable to relieve Sydney

of a portion of the pressure, and to disperse the more turbulent of the

prisoners.

Van Diemen's Land, from its salubrious climate, insulated position, and

its paucity of natives, being considered highly eligible for the erection of

a penal establishment, an officer of the navy, with a body of troops and

convicts, was despatched there with that view, and in August of that year

landed and camped his party on the eastern bank of the river Derwent, at

a spot called by him Rest-down, since abbreviated to Risdon, where there

is now a ferry across the stream.

Early in 1804, an expedition, which had left England in 1802 for the

purpose of forming a penal settlement at Port Phillip on the southern

coast of New Holland, not finding water there, removed to this island,

and felicitously enough fixed upon Sulliven's Cove for their location;

where the first Lieut.-Governor of Van Diemen's Land, Colonel Collins,

landed with a few officers, civil and military, forty-four non-commissioned

officers and privates of the royal marines, and 367 male prisoners;

and where a settlement was founded and called Hobart Town,

after the then Secretary for the colonies. In the same year the river

Tamar, which on the northern coast of the island discharges itself into

Bass's Straits, was surveyed, and a small party of the 102d regiment from

Sydney, under Colonel Patterson, formed a convict station near its

mouth. Launceston, situated about forty miles inland on the Tamar, is the

next large town to the capital, containing at present about 7,000

inhabitants.

Thus Van Diemen's Land is a child of Botany Bay, born when the latter

was still in her teens. The babe of grace continued to thrive, although

very nearly starved to death in its earlier days while still at nurse under

the elder colony — kangaroo flesh being then greedily bought up at 1s.

6d. per pound, and sea-weed (laver, I suppose) becoming a fashionable

vegetable for want of better food. After about three years, however, cattle

and sheep were introduced into the island in considerable numbers, and

were found to flourish exceedingly wherever the most moderate degree

of care was bestowed upon them. Tasmania is a more musical alias

adopted by the island. It has been given in titular distinction to the first

bishop, my excellent and accomplished friend Dr. Nixon, and will

doubtless be its exclusive designation when it shall have become a free

nation.

The ports being closed against any but king's ships, the colony received

but few recruits except by successive drafts of doubly-distilled rogues

from New South Wales. After a few years, however, the interdict against

commerce was removed. Many military officers serving there settled

down on grants of land. A considerable band of emigrants was brought

by the Government from Norfolk Island, when that place was selected

for a penal settlement. Freed prisoners increased and multiplied, and

spread themselves over the interior; but no direct emigration from the

British isles occurred before 1821, when a census being taken, the white

population was found to amount to 7,000 souls. The live stock consisted

of 350 horses, 35,000 horned cattle, and 170,000 sheep; acres in

cultivation nearly 15,000.

In 1824 a supreme court of judicature was established from Home

— judges having thitherto been sent from Sydney to hold occasional

sessions at Hobart Town. In the same year, having attained her majority,

she petitioned for release from the filial ties connecting her with Sydney;

and in 1825 she was by imperial fiat erected into an independent colony.

The progress of the island has been surprisingly rapid; although, like

New South Wales, its prosperity as a colony has been checquered by

occasional reverses, referable perhaps to similar causes — namely,

excessive speculation, rash trading on fictitious capital, extravagance in

living, the common failing of parvenus to wealth, bad seasons, and, in its

early days, the fearful depredations of white bush-rangers and of the

Aborigines. Money must have been plentiful in 1835, when a piece of

land at Hobart Town sold for 3,600l. per acre!

The blacks, never considerable in numbers, and ferocious in their

conduct more on account of outrages received by them from the brutal

convict population, than by nature, were gradually got rid of — chiefly

no doubt by indiscriminate slaughter in fights about their women with

bush-rangers and others, and by the determined steps taken by the local

government for their capture and compulsory location in some secluded

spot, where their small remnant might be prevented from collision with

the Christian usurpers of their country. At one time a sort of battue on a

grand scale was undertaken by the Lieut.-Governor, not for the

destruction and extirpation of the unfeathered black-game, as has been

sometimes unjustly supposed — but for the purpose of driving them into

a corner of the island and so making prisoners of them. Not only redcoats

and police, but gentry and commonalty, enrolled militia-wise, were

brought into the field on this occasion. A grand movable cordon was

formed or attempted to be formed across the whole breadth of the land,

and was designed to sweep the native tribes before it into the “coigne of

vantage” prescribed by the inventor of the plot. It was fishing for

minnows with salmon nets! The cunning blackeys soon slipped through

the meshes, and intense confusion and perhaps some little fright arose

when it was discovered that the intended quarry had got into the rear of

the line of beaters, and was making free with the supplies! This grand

extrusion plan failed, then; — but 30 or 40,000l. of public money was

disseminated through the provinces, and a good many civic Major

Sturgeons got a smattering of “marching and counter marching” that they

will never forget, and that may be of service in the next Tasmanian war.

The poor Aborigines were not the less, in course of time, all killed,

driven away, or secured. Those who fell into the hands of Government

were humanely treated, fed, clothed, provided with medical aid, and

located in a sequestered spot where they might sit down and await — and

where they are now comfortably and most of them corpulently awaiting,

their certain destiny — extinction.

The present native settlement is in Oyster Cove in D'Entrecastreaux's

Channel, an arm of Storm Bay, the mouth of the Derwent. In 1835, the

numbers were 210. In 1842, but 54. In 1848, according to statistics

published by the Royal Society of Van Diemen's Land, the numerical

strength of the natives had fallen to thirty-eight — viz. twelve married

couples, and three males and eleven females unmarried. Thanks to

idleness and full rations, many of them, unlike the wild blacks, have

grown immensely fat — although not fair, nor, as I have just shown,

quite forty!

Among the black ravagers of the rural settlers the most ferocious was a

native of Australia surnamed Mosquito, who had been driven from New

South Wales on account of some outrages committed there. In due time,

however, he was caught and hanged.

18 It will be recollected that the original sentence was “Death.”

19 Omitted

Chapter VI.

HISTORICAL NOTES — FAMOUS BUSHRANGERS — MICHAEL HOWE — FEATS AND

DEATH — CENSUS — PROSPECT IN STORM

BAY — ROADS — A REFORMED PRISONER

— DRIVE TO NEW NORFOLK — THE HOBART

TOWN HUNT — THE SETTLEMENT — SMITH

O'BRIEN'S RESIDENCE — HUMAN

MENAGERIES — THE FEMALE FACTORY — A

LITTER OF BABIES — REGIMEN FOR THE

REFRACTORY — PUSS IN PRISON — PRISON

EMPLOYMENTS — NEW YEAR'S BALL

— DANCING, INFANTINE AND ADULT — GAIETY

AND HOSPITALITY.

BUSH-RANGING commenced in 1813, but was suppressed pretty

vigorously. In 1824 this practice had again attained a fearful height. The

insecurity of life and property, the murders, burnings of houses, stacks

and crops, the robbery and destruction of live-stock, must have seriously

impeded the advance of the colony. The military officers and men took

an active part in hunting down the most desperate ringleaders, and some

of them became famous as gallant and successful thief-takers. Martial

law made short work with those who were captured.

CONTINUED .... read the rest of this article

Extracts from:

Our Antipodes or, Residence and Rambles in the Australasian Colonies, with a Glimpse of the Goldfields

Mundy, Godfrey Charles (1804-1860)

London, Richard Bentley 1852

Source Text:

Prepared from the print edition published by Richard Bentley London 1852

3 Volumes: 410pp., 405pp., 431pp.

A digital text sponsored by Australian Literature Gateway

University of Sydney Library, Sydney 2003

Copyright © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for

commercial purposes without permission

http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/munoura

HMS Havannah Figurehead

Source: sorry, lost link.

HMS Havannah Figurehead

Source: sorry, lost link.