JAMES SPENCE public works contractor

UPPER ELIZABETH St. HOBART

ALDERMEN ELECTIONS Hobart City Council December 1872

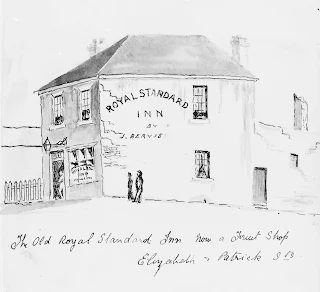

The Royal Standard Hotel, proprietor James Spence from 1862-1874

On the corner of Patrick St. at 142 Elizabeth St. Hobart, Tasmania

Next door to Thomas Nevin's studio, glass house and residence 138-140 Elizabeth St.

Sketch by J. Beavis, Archives Office of Tasmania Ref: NS1013-1-1506

Neighbours at 138-142 Elizabeth St. Hobart.

By December 1872, Thomas J. Nevin's photographic business at 140 Elizabeth St. Hobart (Tasmania) was flourishing. His income from commercial stereography and portraiture, although steady, was augmented substantially with government contracts to photograph prisoners for police records at Hobart's courts and gaols. He commenced the prisons commission in February 1872, followed by a trial period of twelve months after which his commission was renewed for a further fourteen years (14 years from 1872 to 1886). This contract had come about as a result of a visit to Hobart in late January 1872 by the Victorian Solicitor-General Howard Spensley and former Premier Sir John O'Shanassy who recommended to their host the Tasmanian Attorney-General W. R. Giblin to introduce photographic records of prisoners into Tasmanian police offices and prisons. Giblin put forward professional photographer Thomas J. Nevin, a contractor with the Land and Survey Dept since 1868, whose acquaintance they made on January 31st when he accompanied their VIP party of "colonists" on a day trip to to Adventure Bay (Bruny Island). The trip resulted in a series of pleasing and accomplished photographs. Thomas Nevin advised readers of the Mercury, 2nd February 1872, that those group photographs taken on the trip to Adventure Bay were ready and for sale. The Mercury also reported that Nevin's photographs of the event were "very well taken" in the same edition.

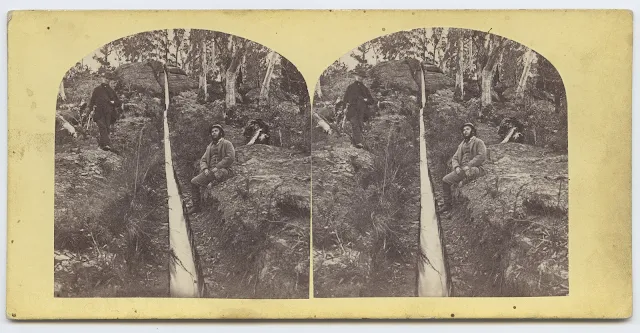

Thomas Nevin had operated as a commercial photographer and government contractor since 1868, when W. R. Giblin acted on behalf of his interests in the dissolution of his partnership with Robert Smith advertised as the firm "Nevin & Smith" at 140 Elizabeth St.Hobart. In June 1872, for example, Nevin provided the Lands and Survey Department with a series of stereographs recording the damage caused by the Glenorchy landslip. As likely as not, he also provided lengthy witness reports to the officials at the Municipal Council, to reporters at the Mercury, and to Public Works Department contractors who regularly gathered at James Spence's hotel The Royal Standard, next door to Nevin's studio, 142 -140 upper Elizabeth St. Hobart Town (looking south from the corner of Patrick St.). As a contractor himself, he would have taken a keen interest in the meetings at which James Spence's cohort of contractors' aired their "grievances received at the hands of the Public Works Department".

Water flow caused by the landslip at Glenorchy, June 1872

Stereograph in arched yellow mount

Thomas J. Nevin, June 1872.

Verso stamped with Nevin's Royal Arms insignia issued by Lands Dept.

TMAG Ref: Q1994.56.2. Verso below

Verso:Water flow caused by the landslip at Glenorchy 1872

Stereograph in arched yellow mount

Thomas J. Nevin 1872.

Verso bears Nevin's Royal Arms government contractor stamp issued by Lands Dept.

TMAG Ref: Q1994.56.2.

The rights of contractors to arbitration, and blatant instances of corruption within the Public Works Department were highlighted in a case of slander brought against contractor James Spence in the Supreme Court, February 1868 (see Addenda below). By then, Thomas J. Nevin was not just James Spence's neighbour who had been operating the public house right next door, the Royal Standard Hotel since 1862 (he paid £1050 for its purchase then), he was also leasing at least half of the property at 140 Elizabeth St. from Spence since 1865, plus a shop front, in what now appears to be a complex sharing arrangement of three premises numbering 140, 138½ and 138 Elizabeth St, which included a glass house and gallery accessed from the street by a side cart path beside the residence at No. 138, owned by builder A. E. Biggs since 1853. Because Thomas Nevin, and Alfred Bock before him, always advertised the address of their photographic premises as The City photographic Establishment, at 140 Elizabeth St. Hobart, they must have paid both James Spence and Abraham Edwin Biggs for two leases - one on the shop at 140 ( James Spence), the other on the site of the glass house which also provided accommodation (removable) at 138½ plus the double-storey residence at No. 138 Elizabeth St. (A. E. Biggs). James Spence sold the Royal Standard Hotel to John Henry Elliott in 1874 for £775 as Lot 1. Included in the sale to John Elliott of Lot 1 was "a cottage and shop adjoining, and three weatherboarded houses in Patrick Street next to Lot 1" for an additional £175. (Mercury 22 Jan 1874 p 2).

Detail of larger photograph -Hobart - view from North Hobart (Swan's Hill)

Callouts here show the rear view of The Royal Standard Hotel at 142 Elizabeth St. Hobart and

Thomas Nevin's studio, glass house and residence, 138, 138½ and 140 Elizabeth St. Hobart

Archives Office Of Tasmania online at PH1/1/35, unattributed, dated 1870

Thomas J. Nevin successfully applied for the full-time civil service position of Town Hall and Office Keeper with the Hobart City Council in December 1875 and shortly afterwards installed his family in the Town Hall Keeper's apartments. James Spence was not so fortunate in his aldermanic campaign to serve on the HCC in 1872. The Supreme Court case in 1868 in which senior public officials mounted a case of slander against James Spence had earned him notoriety as a whistle blower (see Addenda below). One letter to the press even suggested he was ineligible to stand for Council elections because he was under police surveillance and therefore not fit to be in control of police (see A. Ratepayer's letter to the Mercury, 13th December 1872, below)

Election of Aldermen to the H.C.C. December 1872

The press announced the names of four candidates to fill three vacancies in the Hobart City Council elections for Aldermen from September through to the final days of the campaign, 10th - 12th December 1872. Photographer Thomas Nevin had nominated his neighbour James Spence, whose occupation during this election was published as "victualler" although he was also a public works contractor (on waterworks, roads etc) as well as the proprietor of the Royal Standard Hotel which stood on the corner of Elizabeth and Patrick Streets at No.142 Elizabeth St., next door to Thomas Nevin's studio and residence at 138-140 Elizabeth St. Hobart.

Usually, each group of proposers of a candidate would publish a joint statement pledging their support. The Mercury newspaper customarily printed these formal pledges as a discursive solicitation by the supporters, and then provide a lengthy list of their names every week until the close of the election. To be an eligible supporter required social status and assets. Thomas Nevin supported a number of candidates in the course of two decades, and his name appeared regularly below the supporters' pledge. His pledge of support for John Perkins jnr in the 1874 Municipal elections carried his full name Thomas James Nevin - one of the rare instances where his second name - James - has appeared in print.

James Spence, "Mine host" of the Royal Standard Hotel among the nominees

Mercury Sept 10, 1872

TRANSCRIPT

ALDERMANIC ELECTION. - Mr. Spence, "Mine host" of the Royal Standard Hotel", Hobart Town, and also a contractor, has announced himself as a candidate for the Aldermanic seat in the Municipal Council, Hobart Town, vacant by the death of M A. M. Nicol. Mr J. H. B. Walch has been urged to consent to be put in nomination....

Thomas Nevin nominated James Spence as candidate in election

The Mercury (Hobart, Tas.)Tue 10 Dec 1872 Page 2 ANNUAL ELECTION OF ALDERMEN.

TRANSCRIPT

ANNUAL ELECTION OF ALDERMEN.Source: The Mercury (Hobart, Tas.)Tue 10 Dec 1872 Page 2 ANNUAL ELECTION OF ALDERMEN.

NOMINATION OF CANDIDATES.

Yesterday at noon was the last hour for receiving nominations of candidates to fill the vacancies in the City Council caused by the retirement by rotation of Aldermen Belbin, Crisp, and Kennerley. At twelve o'clock the Returning Officer attended at the Courtroom at the Town Hall, and read the following nominations, stating that a poll would be taken on the 12th instant : William Belbin, merchant, of Battery Point, nominated by John Murdoch, Robt. Hawkins, and others. George Crisp, of Campbell-street, timber merchant, nominated by Thos. Giblin, Wm. Crosby, and others. James Spence, licensed victualler, Elizabeth-street, nominated by James Pross, Thos. Nevin, and others. James H. B. Walch, of Macquarie-street, merchant and importer, nominated by D Lewis and James Bett, and others.

Other candidates such as George Crisp, timber merchant of Campbell Street, Hobart, listed more than thirty supporters in his candidate's statement, whereas James Spence's "proposers" in total numbered just five -

James Pross, Elizabeth-street

Thos. Nevin, Elizabeth-street

Fred. A. Fitch, Elizabeth-street

J. Elliott, Elizabeth-street

Wm. H. Payne, Harrington-street.

The outgoing Mayor Alfred Kennerley provided the full list of the nominees and the men who had nominated them in the press on 10th December 1872, detailing each proposer's address in this notice:

TRANSCRIPT:

CITY OF HOBART TOWN.Aldermen elections, Thomas Nevin for James Spence

ANNUAL ELECTION of ALDERMEN.

A List of the Names and Residences of all Citizens nominated for Election as Aldermen for the City of Hobart Town, on THURSDAY, the 12th day of December instant, and the names and residences of their proposers respectively :

1. BELBIN, WILLIAM, Merchant, of Battery Square, Battery Point, Hobart Town, nominated by John Murdoch, Old Wharf ; Robt. Hawkins, Old Wharf ; James Robertson, Old Wharf ; Saml. O. Lovell,Patrick-8treet ; John Pregnell, Macquarie-street ; Edward Espie, De Witt-street ; Moses Cohen, Old Wharf ;, James Macfarlane,New Wharf. I

2. CRISP, GEORGE, of Campbell-street, Timber Merchant, nominated by Thos. Giblin, 49, Macquarie-street ; Wm. Crosby, freeholder, Davey-street ; Askin Morrison, Freeholder, - New Wharf ; Isaac Wright, New Wharf ; John Murdoch, Old Wharf ; James Thomas Robertson, Liverpool-street ; M. F. Daly, Liverpool-street ; Albert Gaylor, Liverpool street ; W. H. Burgess, jnr , Liverpool-street ; James Bett, I . Murray-street;James McPherson, Freeholder, Argyle mid Melville - streets ; Edward Ash, CO, Elizabeth-street ; Israel Hyams, Freeholder, Elizabeth-street ; A. G. Webster, Old Wharf ; James Morling, Freeholder, Old Wharf ; Peter Oldham, Householder, Argyle-street ; Thomas Mackey, Freeholder, Battery Point ; Neil Lewis, Collins-street ; George Brown, Leaseholder, Elizabeth-street; William McFarquhar, Liver-pool-street ; Philip O'Reilly, Freeholder, Murray-street ; D. R, Bealey, Householder, Murray-street ; Wm. Bealey, Householder, Murray-street ; H. J. Marsh, Leaseholder, Murray-street ; O. H. Hod berg, Argyle-street ; C. F. Creswell, Freeholder, Murray street ; John Paget, Park street ; D. Murphy, Liver-pool-street , Frederick Fitch, Elizabeth-street ; William Hamilton, Freeholder, Elizabeth-street ; Wm. Walton, Collins-street ; James Robert-,' '' son, Campbell-street ; John Pregnell, Macquarie-street ; S. 0. Lovell, Patrick street ; Wm. Barnes, Freeholder, Harrington-street.

3. SPENCE, JAMES - Licensed Victualler, Elizabeth-st, Hobart Town, nominated by James Pross, Elizabeth-st. ; Thos. Nevin, Elizabeth-street ; Fred. A. Fitch, Elizabeth-street ; J. Elliott,Elizabeth-street; Wm. H. Payne, Harrington-street.

4. WALCH, JAMES HENRY BRETT, of Macquarie - street, Hobart Town,Merchant and Importer, nominated by David Lewis, Hampden Rood ; James Bett, Murray-street ; George Din ham, Cromwell-street.Battery Point ; Alex. McGregor, Cross -street, Battery Point ; Geo. Salier, Elizabeth-street ; Jas. Harcourt, Elizabeth-street.

Given under my hand at Hobart Town aforesaid this 9th day of December, 1872.

ALFRED KENNERLEY, Mayor of the City of Hobart Town.

The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 - 1954) Tue 10 Dec 1872 Page 3 Advertising

Hobart Town Hall with figure at front, poss. the keeper Thomas Nevin

No date, ca. 1876-80, unattributed, half of stereo

Archives Office of Tasmania Ref: PH612

James Spence's promise to be "a dog on the chain"

As an experienced public works contractor, James Spence's promise to the citizens of Hobart, if elected, was to monitor excessive expenditure on upcoming water and road infrastructure projects. He suggested too - and this proved to be his undoing - that he would investigate and report corruption within government, whether local or colonial, or as he so picturesquely put it: -

I should consider myself as a dog on the chain, always watching, ready to bark and bite if required, to protect the rights and privileges belonging to the Citizens of Hobart Town.

James Spence's promises if elected as Alderman

The Mercury (Hobart, Tas.) Wed 11 Dec 1872 Page 3 Advertising

TRANSCRIPT

TO THE CITIZENS OF HOBART TOWN.

GENTLEMEN,

I have received so many promises of support, before and since my nomination, for one of the vacant scats in the Municipal Council, that I think I should be wanting in respect to these gentlemen did I not go to the poll.

I therefore submit myself to the citizens, to bo dealt with according to law and usage in all elections.

And as many works of importance will be brought before the Council during next year, such as the Creek, Waterworks, and Cesspools throughout, the town, which will cost large sums in their construction here my experience as a Contractor might be the saving of hundreds of pounds to the inhabitants.

Should I be returned by you as one of your Aldermen I should consider myself as a dog on the chain, always watching, ready to bark and bite if required, to protect the rights and privileges belonging to the Citizens of Hobart Town.

I have the honour,

Fellow Citizens,

To remain your obedient servant,

7684 JAMES SPENCE.

Hobart Reservoir in making

Publication Information: Hobart : s.n., c1870.

Physical description:1 photograph : sepia ; 20 x 24 cm

Archives Office Tasmania

View online: https://stors.tas.gov.au/AUTAS001126185735w800

Photograph of Waterworks troughing, Hobart, Tasmania, before 1870.

UTas ePrints: Link: https://eprints.utas.edu.au/3554/1/waterworks-3.jpg

Public scorn poured on "the dog on the chain"

Responses to James Spence's appeal to the public for their trust were negative, if the press was to be believed.

James Spence "dog on the chain", not fit for public office

Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 - 1954), Thursday 12 December 1872, page 3

TRANSCRIPT

ANNUAL ELECTION OF ALDERMEN.James Spence "dog on the chain", not fit for public office

TO THE EDITOR OF THE MERCURY.

SIR, - Adverting to the address to the citizens signed James Spence, I cannot but think that a becoming regard for the preservation of the dignity of the Aldermanic office will most effectually be manifested on the present occasion by the election of Nos. 1, 2, and 4, leaving it to No. 3 to provide " a dog on the chain" for such locality as most needs canine protection.

Hobart Town.

Your obedient servant,

ELECTOR.

11th December, 1872.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE MERCURY.

SIR,-As a question of principle is involved in the present election, I wish to express my opinion that any man whose business is under the surveillance of the police is not fit to have control over that body. I have no personal objection to Mr. Spence, but for the foregoing reasons cannot vote for him.

A. RATEPAYER.

Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 - 1954), Thursday 12 December 1872, page 3

Of note in the following article announcing the results of the election is the mention of James Spence using election posters which were most likely designed and printed in Thomas Nevin's studio next door. Cartoons were a traditional means to voicing contentious opposition. This poster, for example, plastered on walls around the town during the July 1875 Hobart Municipal elections, suggested strongly the corruptibility of each candidate. With nicknames to suit, they were depicted as rats hovering around a caged bag of money containing a specific sum for reasons best known to insiders.

The satirist's caption reads:

BARRACOUTTA Bill - Will he take think you?Source: Archives Office Tasmania

GLIBTONHUE - Certain, Phil but 'Care here he comes!

SIR ALFRED - Why, he must be starving, how thin he's got?

SAW DUST - You needn't close the trap from Tom. He'll stay as long as the bait lasts

TEA & SUGAR TOMMY - The rascal doesn't even pick his steps he's in such a hurry

CAVE VANEM - What a horrid dirty road. It's well I'm use to such ways.

View online: https://stors.tas.gov.au/AUTAS001124070897W800

Women, of course, did not have the right to stand for aldermanic service on the Council, let alone the right to vote in these elections. The reporter in this article seemed to find so normal the lack of women's suffrage as a target of humour, he took the opportunity to tell a probably fictional story of an incident at the polling booth whereby a stereotypical hen-pecked husband tried to rush off home with his unmarked ballot paper because he was under orders from his wife to consult with her first on which candidates he should choose.

TRANSCRIPT

THE ELECTIONS.Source: The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 - 1954) Fri 13 Dec 1872 Page 2 THE ELECTIONS.

HOBART TOWN.

The polling for three aldermen to fill the vacancies in the City Council took place yesterday. The candidates were two of the retiring aldermen - Messrs. William Belbin and George Crisp - and Messrs. J. H. B. Walch and James Spence. The polling commenced at nine o'clock, and until four o'clock, when the ballot-boxes were closed, there was a large number of people congregated in front of the Town Hall. The respective merits of the candidates were freely discussed and criticised, and assertions as to the result were numerous. There appeared to be a pretty general belief, however, that the retiring aldermen and Mr. Walch would be the successful candidates. Mr. Spence has tried to gain an aldermanic seat before, and from the position he stood in at the last election, when Alderman Cook was returned, his friends were confidant of his success. He was the only candidate who indulged in the luxury of posters, and on one of them he intimated to the ratepayers that he was the friend both of the rich and the poor, and that he would save them from fresh taxation. This small piece of bombast caused no small amusement ; and this, added to that unique idea of Mr. Spence's that he would consider himself as a "dog on the chain, always watching, ready to bark and bite," placed the candidate in a somewhat ludicrous aspect. All the candidates were within the precincts of the Town Hall some part of the day. Mr. Walch did not appear to exert himself as much as the other three candidates, for each of whom a cab was busily engaged in bringing ratepayers to poll. The voting was made in the Mayor's Court, and the Returning Officer, clerks, and scrutineers were kept tolerably busy the whole time. At times there was a cessation of business, but a rush of voters soon after would cause some stir. The whole of the proceedings were carried on in a very quiet and orderly manner. One ratepayer caused a little amusement during the morning. After receiving his ballot paper he was marching out, when his progress was stopped at the door by a member of the police force, who interrogated him as to where he was going. " Home to my wife," said the man, " to ask her whom I shall vote for." His interrogator suggested that he had better go and record his vote, and never mind his wife.

" But if I don't ask her what I am to do she'll blow me up," from which it is to be inferred that the wife had certainly got the upper hand of her husband. No approximate estimate could be obtained of the number of voters who polled, though it is said it will be much smaller than at the annual election last year. The number of ballot papers then was 950, out of a total of 3049 voters on the roll. At this election the number of citizens entitled to vote is 3,140, the different classes being as follows .-1 vote, 2,434 ; 2 votes, 436 ; 3 votes, 108 ; 4 votes, 35 ; 5 votes, 10 ; 6 votes, 10 ; 7 votes, 7. Alderman Pearce was at the head of the poll last year with 761 votes ; then came Alderman Green with 730 votes ; Alderman Risby, 669 ; Mr. Lovell, 636 ; Mr. Robertson, 333. At the election to fill up the vacancy caused by the death of Alderman Nicol, Alderman Cook was successful with 775 votes, Mr. Spence being the next with 559.

The Mayor acted as Returning Officer, and was assisted by Alderman Risby and the Town Clerk. The poll clerks were Messrs. Robb, Carmichael, H. R. O. Wilkinson, A. G. Pogue, James Allon, and John Cooper.

At four o'clock the doors were closed, and the ballot boxes sealed up. Shortly after that, the Mayor announced on the steps of the Town Hall that the ballot boxes would be opened at 10 o'clock this morning, and the result of the poll declared about noon.

The reporter in what follows got well and truly entangled in his own in bombastic ridicule about the "dog on the chain" conceit used by James Spence, punning his way to absurdity well beyond Spence's meaning and resolving it with a quotation from Shakespeare, the last refuge of course of the impotent self-righteous. His real concern, so it appears, was the impact Mr Spence's intentions might have on tourism.

Ridiculing James Spence's candidacy as a "dog on the chain"

Extract; article link at Trove

Source: The Mercury (Hobart, Tas.)Thu 12 Dec 1872 Page 2 THE MERCURY.

TRANSCRIPT

THE citizens are called co to-day to elect three Aldermen to supply the places of Mr. Kennerley (the Mayor), and Aldermen Belbin and Crisp, who retire by rotation. The Mayor does not seek re-election. The other two gentlemen are candidates, as are Mr. James H. B. Walch, and Mr. James Spence. We never had any doubt as to which are the most fitting men, and as little did we doubt as to which three the citizens will elect. But could there have been any doubt, Mr. James Spence has left no room for it. If the citizens are not lost to every sense of decorum, Mr. Spence must have thrown away whatever chance he had. We know not whether that gentleman meant to indulge in something very severe, or merely intended an effort at wit. But he has only succeeded in making himself ridiculous by his attempt to bring in the Council, and through the Council the City, into contempt. The Town Hall is not a kennel, nor the Council burglars to be kept at bay by a mastiff. We want in the Council gentlemen of some position and business habits, and not one whose highest aim it is to be compared to " a dog on the chain;" and as he says he will be always watching, ready to bark and bite if required, we would recommend his friends, as his barking would probably be as great a nuisance as is the bellowing of calves, of which we a few days ago had to complain, to take care that his chain be as short as possible. In this way his bark will be less heard, and except some over-daring people should go within the reach of his chain, there would be no danger of his biting anyone. The intimation Mr. Spence has given of his intention should not be neglected. Hydrophobia has not hitherto shown itself in Tasmania. But there is no saying what may be the consequences to a " dog on the chain," whose thoughts are so much occupied with the " Creek, Waterworks, and Cesspools." As the warm weather is now coming on, the danger is the greater, and its risk will be so much extended by the large influx of strangers from the other Colonies, that we have little doubt that should the citizens elect one who, if returned as one of the Aldermen, would consider himself " as a dog on the chain, always watching, ready to bark and bite," the dangerous freak of the citizens would be at once flashed across the Straits, and along the wires through the neighbouring Colonies. Our intending visitors would seek some other place of spending their holidays, for what sane invalids or pleasure seekers would, in addition to risks from native devils, venture to put their feet on shore on the wharfs of a city where a dog in authority is kept ever on the chain, ready to bark and bite if required, the chained Newfoundlander being of course the only judge as to when he should bark, when bite, or when be a dumb dog. The danger is too great to be risked. The City Council has no use for such an animal. And if it is not a kennel, it must not be made one. But if Mr. Spence must find a sphere of usefulness, perhaps Mr. Graves, who has lately been so unlucky in his exportation of devils, will again tempt luck, and send him across to " Punch," the last impression of that celebrated character's dog in " Punch's Almanac for 1873 " being rather in danger from the awkward position of a Cockney sportsman's gun. If this mode of disposing of the " dog on the chain " cannot be followed out, probably the citizens will accept the candidate's other alternative, and "deal with him according to law and usage in all elections," and leave him nowhere on the poll, that being the " law and usage " in all cases where candidates, ' instead of showing themselves possessed of qualifications, make themselves ridiculous, or seek to make fools of others. Mr. Spence's address can have only one result, for, as Shakespeare wrote, just as if be had had Mr. Spence's address in his mind's eye,Source: The Mercury (Hobart, Tas.)Thu 12 Dec 1872 Page 2 THE MERCURY.

" What valour were it, when a cur doth grin,

For one to thrust his hand between his teeth,

When he mlght spurn him with his foot away !"

The Election Result

James Spence failed in his bid to serve as Alderman on the Hobart City Council. The day of the election result, 14th December 1872, he advertised in the Mercury the lease on the Royal Standard Hotel and his farm at Constitution Hill, no doubt to escape further attention in the press and recoup costs of his election campaign.

TO LET, "THE ROYAL STANDARD, " Elizabeth-street. Also a farm of 1,308 acres at Constitution Hill, with a good house and outbuildings complete. Apply at once to JAMES SPENCE.Below is the speech James Spence gave as the rejected candidate. He made one last valiant effort to explain what he was trying to say when he promised voters he would act as "a dog on the chain". He meant, he said, that he would "protect the rights and privileges belonging to the citizens of Hobart Town....".The problem was, James Spence had a history of playing the insider whistle blower going back to allegations he made in 1867 of misappropriation of timber from Port Arthur that was refashioned for public officials' personal use and at the Hobart Town Hall no less; of missing metals and materials for main line development at the Bridgewater causeway; and of offers made to him personally amounting to bribery to take money and keep quiet about it all. He was taken to court in January 1868 on charges of slander, for which he had to pay damages. The same charges were looming again, simply because of a colorful conceit: to be "a dog on the chain" for the citizenry of Hobart Town (see the full trial transcript of the Supreme Court Civil sitting, 28th January 1868, below - Addenda 3:)

Of course, allegations such as James Spence's of gross misconduct on the part of public officials would come as no surprise a few years later to his supporter Thomas Nevin, who had to contend with the notoriously corrupt Mr. W. H. Cheverton, the figure at the centre of James Spence's allegations, when contractor Thomas Nevin with his close friend and colleague Samuel Clifford were requested by Parliament in July 1873 to pay a visit to the Port Arthur prison site to photograph the ruinous state of the buildings and surrounds. William Cheverton used his dual roles of Inspector of Public Works and private contractor to please himself. He had the publicly reviled prison Commandant A. H. Boyd in his pocket, and by December 1873, when each was found to have shared the spoils of embezzlement of public funds after they provided Parliament with false reports on the need for massive expenditure at Port Arthur,they were summarily dismissed from public office. A. H. Boyd even published a letter in the press begging the government to compensate him for dispensing with his services (Mercury, 9 May 1877). So, James Spence might have failed to win public confidence in 1868 or 1872, yet his outspoken efforts on behalf of contractors who stood up to the power exercised by corrupt public officials must be viewed as an important contribution to the emergent union movement.

Extract from James Spence's speech on failing to gain an aldermanic seat in the Hobart City Council

Mercury (Hobart, Tas. :), Saturday 14 December 1872, page 2 See TRANSCRIPT below

TRANSCRIPT

THE ELECTIONS.James Spence's speech on failing to gain an aldermanic seat in the Hobart City Council

HOBART TOWN.

The result of the polling for the three aldermen for the City Council was declared yesterday. The ballot boxes were opened in the presence of the Returning Officer at 10 o'clock, and more than two hours were occupied in going through the ballot-papers. The result of the election confirmed the general belief. At about half-past 12 a large crowd had assembled out-side the Town Hall, and the Mayor came out, and, standing at the door, began to announce the result, but cries were heard from persons in the street, to " come on the steps," It was suggested, however, that an adjournment to the large hall upstairs should be made, and accordingly this was done.

The MAYOR then read the state of the poll as follows :

No. of Votes.

Crisp 1037

Walch 883

Belbin 864

Spence 562

Informal papers. 26

He declared Messrs. Crisp, Walch, and Belbin duly elected as aldermen of the city.

Mr. CRISP said he appeared before them again-he said again, because that was the fifth time he had had the honour to be elected as an alderman of the city. He felt flattered beyond description to think that, after 12 years' service, the electors still had confidence in him, and that they had not forgotten past services. It was not his intention to come forward on the present occasion, but he was induced to do so by many of his friends, and he could assure them it would be his constant endeavour to do what was right and straightforward for the good of the citizens. He again thanked them, and hoped that, at the end of the three years, they would have no cause to regret having given him support. (Applause.)

Mr. WALCH said he felt highly the honour they had conferred upon him by electing him as a representative in the Municipal Council. They had placed him in a good position on the poll, and in doing so showed the confidence they had in him, although he was an untried man. The Municipal Council, he continued, had no political power, no control over the affairs of the State, but there were responsibilities attaching to the position of alderman in attending to the welfare of the city. Nature had done a great deal for Hobart Town, with its scenery, its beautiful harbour, and many other good things of this world, and it was their duty to I make use of the benefits which had been bestowed upon them, for casual visitors who may come here, and still much more their duty to make it pleasant for the people who had taken up their residence permanently in this city. He had been a resident a great many years ; his face was familiar to many of them. He had seen the stream flowing through the heart of the city year after year, and he had a claim to be elected alderman. He was quite new to public life, but he should endeavour to steer a straightforward course, and act on the advice given by the great Cardinal Wolsley to Cromwell

" Be just and fear not,

Let all the ends thou aims't at be thy country's,

Thy God's, and truth's." (Cheers.)

Mr BELBIN said he was proud of his position, although he was not at the top of the poll as on the last occasion. He could only promise, while he had the honour of a seat in the Council, to do his best for the interests of the whole city, as he had always endeavoured to do.They might be assured of this that during the present year rigid economy would be exercised in the management of the finances. There were many pressing things coming upon the city, and if the police were thrown upon the local bodies, increased taxation was staring them in the face. It was an unpleasant position for aldermen to suggest extra taxation, but they might be assured that he would give his best attention to all things which came before the aldermen. He would gladly have retired from that position. He believed there were many citizens who ought to come forward ; and he did not think the same men ought to be continually occupying the aldermanic chairs. He again thanked them, and sat down amid applause.

Mr. SPENCE then said : Fellow citizens of Hobart Town, I am again before you as a rejected candidate for the office of alderman, and I have to thank every one that has voted for me this time, as also these who have voted against me. I believe they think they have put in a better man, and they have a right to think so. Two of them have been in for years, but I am not of the same opinion as they are. I am of opinion that no alderman should serve for more than three years at one time, and thus cliques would be avoided. For this reason it was that I came before you. I believe that I could be of service to the citizens, from my practical experience as a contractor in this town. I believe that the citizens' money should be laid out for the benefit of the citizens, in streets and waterworks, and that my practical experience might have been of some benefit. Still, as you have kept me out of it, it will be better for me, and to come before the citizens as a contractor I may be more useful to them than I should be as an alderman. Gentlemen, I intend to say little owing to the place you have put me in. It will be the last time that I will come before you (hear hear) because of others asking me. If I come again it will be my own action. I have to explain myself with regard to certain words contained in my address, and on account of which I have been taken to task by The Mercury. On Thursday week The Mercury complained of the remissness of the aldermen in permitting certain butchers to keep bellowing calves on their premises at night. On the Saturday following attention was called to the action of the Cemetery Board in depriving the citizens of certain privileges, and in my address I referred to these matters, stating that " should I be returned by you as one of your aldermen I should consider myself as a dog on the chain, always watching, ready to bark and bite if required, to protect the rights and privileges belonging to the citizens of Hobart Town." The Mercury commented severely on this, though what I meant was that, if the citizens' privileges were invaded, every alderman should be as a watch dog on a chain to watch and protect the interests of the citizens. The Mercury, however-[The citizens at this point in Mr. Spence's address commenced to leave the hall in a stream, evidently tired of the subject.] I thank you again, gentlemen, for the support you have given me. I thank you all now and for the last time. (Applause.)

On the invitation of Alderman Crisp three hearty cheers were given for the Returning Officer; three cheers were then given by desire of his Worship the Mayor for "The Queen," and the proceedings terminated.

Mercury (Hobart, Tas. :), Saturday 14 December 1872, page 2

Photographs of Public Works

Photographers Thomas Nevin and Samuel Clifford documented public works on commission. Work on the sites in these photographs was most likely tendered for by James Spence, and completed by his sub-contractors. He may have used the photographs for evidence of work completed, or indeed work neglected by PWD officials.

RESERVOIR NEW WATERWORKS 1867 (Hobart, Tasmania)

Reservoir, new waterworks

Publication Information: ca. 1867.

Physical description:1 stereoscopic pair of photographs : sepia toned

Archives Office of Tasmania

View online: https://stors.tas.gov.au/AUTAS001124851304w800

Photograph of Stony Steps or Waterworks Valley, Hobart, Tasmania with Livingstone's house Marydale in the foreground and the Waterworks dam in the background, c.1870.

UTas ePrints. Link: https://eprints.utas.edu.au/3553/

THE CAUSEWAY at BRIDGEWATER (Hobart, Tasmania)

Undated and unattributed, this photograph was taken to show the railway line crossing the causeway on the River Derwent at Bridgewater, north of Hobart, Tasmania. Missing public money which was supposed to pay for the construction of this causeway was another "last straw on the camel's back" that prompted James Spence to convene a meeting of contractors to air complaints about corruption within the Public Works Department (see Addenda below, Meeting, 3 December 1867).

Photograph - Bridgewater causeway, view towards eastern shore

Item Number: PH30/1/6954

Start Date: 01 Jan 1870

Archives Office Tasmania

View online: PH30-1-6954

AQUEDUCTS and CHANNELS

Troughing - Hobart, Water Works

Publication Information:

Hobart : s.n., c1870.

Physical description: 1 photograph : sepia ; 19 x 24 cm

View online: https://stors.tas.gov.au/AUTAS001126185594w800

Archives Office Tasmania

Aqueduct Waterworks, Fern Tree Inn

Publication Information: ca. 1865.

Physical description: 1 stereoscopic pair of photographs : sepia toned

Archives Office of Tasmania

View online: https://stors.tas.gov.au/AUTAS001128189800

The Waterworks at Ferntree;

The man in the background resembles the Mt Wellington resident and guide, Mr Wood.

The man in the foreground may be a contractor admiring his new channel, or he may be just a tourist.

Publication Information: ca. 1865.

Physical description: 1 stereoscopic pair of photographs : sepia toned

Archives Office of Tasmania

View online: https://stors.tas.gov.au/AUTAS001128189792

Addenda: press reports of meetings and court sittings

Addenda 1:: 3rd December, 1867: Notice published in the Mercury about allegations of corruption made by James Spence at a meeting at his hotel, The Royal Standard:

TRANSCRIPT

THE CONTRACTORS' MEETING. - The Government, we understand, called on Mr. Spence to substantiate the charges he made against the Public Works Department at the contractors' meeting on Monday evening last. Some of the parties reflected upon that meeting have also, we hear, served Mr. Spence with notice of action for what he then said. How these two modes of proceeding will work together, we do not well see.

Addenda 2:: 3rd December 1867. A lengthy report of the meeting was published in The Tasmanian Times, detailing names, places, specific instances of jobbery, embezzlement and bribery. Jobbery is the practice of using a public office or position of trust for one's own gain or advantage (Oxford Lexico)

THE CONTRACTORS AND THE PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT.

A public meeting of Contractors, called by advertisement, took place last night at the Royal Standard Hotel, Elizabeth-street. There were present, Messrs. James Spence, A. M Nicol, Seabrook, Wiggins, Pross, Smith, and others. Mr. Seabrook was voted to the chair, and read the advertisement calling the meeting. It appeared from what took place that the contractors complain of a number of grievances received at the hands of the Public Works Department, and that the last straw on the camel's back arose as follows:—On the 12th November, tenders were called for the supplying of 3000 cubic yards of metal for thee main road. Five tenders were sent in, McDermott's at 8s.; Spence, 10s. ; Martin, 9s. 6d; Davidson & Marshall, 10s. 6d.; and M. C. Stalles, 10s. 6d. Some disturbance or unpleasantness arose on the opening of the tenders, and McDermott withdrew his tender. The usual practice has been in these cases that the next tender as to price should be the accepted one. In this instance, however, the Director of Public Works called for fresh tenders, and on the 21st November, the invitation appeared, but with a new clause in the conditions. The new clause was printed in italics, and ran thus—" A marked cheque payable to the Director of Public Works and Roads for a sum of £50, or a like amount in cash, must accompany each tender, as a guarantee that the same is bona fide. Which amount will be forfeited to the Government should the party tendering fail to comply with the conditions under which the tenders are hereby invited. On compliance with the conditions of the tender, the sum of £50 will be placed to the credit of the deposit hereinafter required to be made. On the 27th November the tenders were again opened, and McDermott, after having withdrawn his tender in the first instance, again tendered at 8s and was accepted. Mr. Spence entered his protest against McDermott's tender being accepted after having once been withdrawn. To that protest Mr. Spence received the following reply:— "Public Works Office, " 30th Nov., 18677. " SIR,—I transmitted to the Government, with the Tenders received on the 27th inst., under the re-advertised conditions of the 21st Nov., your protest, and have to acquaint you that the lowest tenderer having complied with re-advertised conditions, the Government do not consider it should entail upon the Public Treasury a loss of £143.15s., by falling back upon a higher tenderer.

I am Sir, Your very obedient servant,

(Signed)

" W. R. FALCONER,

" Director of Public Works.

" To Mr. James Spence, " Elizabeth-street."

Mr. Seabrook then addressed the meeting at considerable length, on the wrongs the contractors had been subjected to by the Public Works Department. He said he must regret that there were not more of the contractors present that evening. It showed a great dereliction of their duty to themselves and families. He had often felt himself placed in an invidious position by the public works department, and those in charge of it. He had been a contractor for upwards of 30 years. Formerly it had been the rule to call for tenders for all works over £10, but that salutary rule had been departed from. He said there had been rank jobberyshown in the erection of the slaughter houses. He referred to the former Director of Public Works, Mr. W. P. Kaye, who, he said was an honest man, but who had been ousted by the clique which got into the department. The appointment of the present Director of Public Works, by the Ministry of the day had at the time been received with applause, but it had proved a heavy curse to the colony. The appointment of the Inspector of Public Works had followed, and the result had been a clique that had cost the government thousands and tens of thousands of pounds. He did not like to see men overridden by a petty tyrant. He said that the whole of the transactions of this clique were nothing but a bed of filth arid dirt. Look at the Bridgewater Causeway. A £1000 of work had there been shirked. The superintendent of that work, Mr. Grant had refused to certify to the work of the contractors, Messrs. Cheverton and Andrews, and yet Mr. Falconer stepped in and gave the certificate so as to enable Messrs Cheverton and Andrews to get their money, and yet at this very time Mr. Cheverton was the Inspector of Public Works. Now through the Inspector of Public Works being in partnership with the Contractor the public had been put to the expense of Mr. Grant's salary of £3 or £4 a week for 18 months, while the Inspector was drawing his usual stipend. Mr. Grant refused to give the certificate and never did give it, but the Great Mogul of the Public Work's department stepped in and nearly a thousand pounds worth of work was paid for which was never done. If public officers were capable doing their duty faithfully, they would not allow any deviations from specifications for friends or foes. A report on this subject had been made by the Public Contractors to the Government, but without any redress, and it was now time to speak out. Cheverton and Andrews had amassed a large amount of riches, and it appeared that now a certain amount of money must be sent in with all tenders for Public Works and the effect would be throw all the contracts into the hands of these parties. A tradesman had enough to do to find the necessary money for carrying out the contract when obtained, but if he had to find a deposit as well as to leave twenty-five per cent, of his money in the hands of the Government, it would be a great hardship. He reviewed the question of the stone and other materials on the ground being a security to the Government for the contractor's performing his work according to the conditions. He said that there were a great many malpractices in the department, and they (the contractors) had a right to be fairly dealt with.

Mr. James Spence had called that meeting because he thought these matters ought to be considered. He had hoped to see more persons there. There were other matters connected with the contractors in general which he should speak on. Some present now had been present at the meeting in 1863, when it was carried that a clause should be inserted in all contracts providing for arbitration, and that none should tender unless the clause was agreed to. But he found others had evaded the question, and he had been obliged to follow suit. Mr. Spence mentioned the difficulties be had had with the Director of Public Works in respect to his (Mr. Spence's) claim for £1500 odd for the work on the main road, and which the Director of Public Works had refused to pay, and knocked him off on the ground that his work was not done according to contract, and read a number of letters referring to the same; and yet the arbitrators had—after a deal of trouble in getting arbitrators appointed—delivered an award in his (Mr. Spence's) favor, with £25 costs, and thus exposed the incorrectness of the Director of Public Works' judgments. He referred to some election matters, and said he was told once that if he did not allow himself to be placed on Mr. Wilson's committee be would only increase his difficulty with the Public Works department. The Director of Public Works had also told his (Mr. Spence's) banker that he would never get one penny of the £1500. He would now move the resolution he had proposed. It was: "That the contractors feel alarmed at the Director of Public Works, introducing a clause into tenders to compel persons tendering to send in a sum of money with their tenders, as it will prevent many fitting persons from tendering." Mr. Spence recapitulated the last special grievance with respect, to these last tenders, and stated the action he took at the time and its result. He said that what had taken place would lead to the impression that there was a connection between certain parties in the Public Works Office, and tliat this claim was put in to enable legitimate contractors to be kept out. He never liked to run down either public or private men, but sometimes it could not be avoided. Mr. Cheverton had made him an offer, that if he (Mr.Spence) would keep silent about the Bridgewater affair, he (Mr. Cheverton) would let him have all on the main line of road. In the contest between Mr. Chapman and Mr. Crowther something had come up about a quantity of timber from Port Arthur, and the Auditor had called for an account of what had become of it. He (Mr. Spence) had a paper in his secretaire that would throw some light on it. He could find carpenters who had been employed at night sawing off the government brands, and he could even place his hand on some of the timber now with the government mark on it. It had gone into the new building at the Town Hall, and the profits, as a matter of course, into the pockets of the " Long Company!" If a proper investigation was made into that public office, not Cheverton, Falconer, nor Grey would be there one day. He only wanted justice. He could not see that any public body should be shown favor or affection. Mr. Spence remarked on the Director of Public Works' statement in Parliament on the difference between the work on the Huon Road, done under the Public Works, and that done on the contract system, and procured thereby the expenditure of a sum of money through that department instead of the survey department. After some further remarks, Mr. Spence said he had heard the Treasurer say to Mr. Falconer that day, in connection with another arch to be erected, that "he must have plans and specifications as he wanted no more jobbery. The resolution was then put to the meeting, being seconded by .Mr. Joseph Smith and carried unanimously. It was then moved by Mr. A. M. Nicol, and seconded by Mr. Wiggins, " that the resolution just passed be embodied in a petition to the Governor and the Executive Council, praying that the council will please to consider the grievance complained of and give such relief as they may think fit." This was also carried unanimously, and after a vote of thanks to the Chairman, the meeting separated, Mr. Spence undertaking to get the petition drawn up and signed.

Source: The Tasmanian Times (Hobart Town, Tas. : 1867 - 1870) Tue 3 Dec 1867 Page 3 THE CONTRACTORS AND THE PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT.

Addenda 3:: 29th January, 1868. The Supreme Court Trials, whereby three plaintiffs - Cheverton, Falconer and Gray - brought a case of slander against the defendant James Spence. Jury and bench verdicts awarded nominal damages against James Spence, not the £1000 sought by William Cheverton who did not make a personal appearance. Newspaper reporters were questioned by both sides as to the relative accuracy of their note-taking from speeches made at James Spence's gathering of contractors at the Royal Standard Hotel; for example, if they used shorthand (supposedly verbatim) or longhand (written after the event); or if they reported the speeches in the first person (conveying the speaker's subjective viewpoint) or in the third person (assumed objectivity from the listener's viewpoint).

CHEVERTON v. SPENCE

LAW.

SUPREME COURT.

CIVIL SITTINGS.

TUESDAY, 28TH JANUARY, 1868.

BEFORE His Honor Sir Francis Smith, Knt.,

Judge, and special juries.

CHEVERTON v. SPENCE.

Jury : Thomas Macdowell (foreman), Thomas Marshall, John Mezger, William Murray, G. R. Napier, R. B. Murdoch and Edward Moore.

The Solicitor-General appeared for the plain-tiff, instructed by Mr. Westbrook, and Mr. Cansdell for the defendant, instructed by Messrs. Crisp and Gill.

The Solicitor-General in opening the case read the declaration, which alleged that the plaintiff was inspecting officer and overseer in Her Majesty Public Works Department, and that the defendant had spoken and published of and concerning the plaintiff in his said office the words following, that is to say : Some of these people (meaning thereby the plaintiff and other persons), have made one thousand pounds out of the Bridgewater contract, (meaning that the plaintiff acting in combination with other persons had wrongfully received the sum of one thousand pounds in respect of a contract which the defendant thereby insinuated and meant to be understood, had been entered into by the plaintiff and others for the repair of the Bridgewater Causeway on the main line of road, between Hobart Town and Launceston). I have had offers preferred to me from that office, (meaning corrupt offers from the plaintiff). Mr. Cheverton, (meaning the plaintiff), and the late Mr Gowland came to me (the defendant), at the last Champion Races and said, " Oh, Mr. Spence, say nothing about this work, and you will save us (meaning the plaintiff and the late Mr. Gowland) five hundred pounds. If you do this you can have anything you like on the main line of road" I told them (meaning the plaintiff and Mr. Gowland), I did not do business in that way, (meaning that the plaintiff proposed to the defendant that if the said defendant would say nothing further to the Bridgewater commissioners about the said work, the defendant having previously complained to the said commissioners of the manner in which the said work had been performed, the plaintiff would wrongfully and corruptly endeavour to obtain for the defendant certain contracts from the government of Tasmania for the repair of the said main line of road.) Also for having spoken and published of the defendant the following words:- "He referred to a quantity of timber which had come from Port Arthur, and which had not been accounted for to the Auditor. He could tell where the timber was. He could show people the Government brand on it now, and could produce carpenters who had been employed night after night sawing off the ends of that timber, a great quantity of which had been worked up in the Town Hall. (Meaning the Town Hall in Hobart Town aforesaid.) There should be an investigation into these matters, and if there was neither Falconer, Cheverton, nor Gray would be in that office. The money for that timber had gone into the pockets of that company. (Meaning thereby that the money for which it was insinuated the said timber had been sold had been in fact and corruptly received by the said Wm. Rose Falconer, Wm. H. Cheverton, and James Gray.) We want honest men in that department, (thereby meaning it to be under-stood that the said William Rose Falconer, the plaintiff, and James Gray, being officers in the said Public Works Department, were not honest men). The plaintiff claimed £1000 damages. To this the defendant had pleaded the general issue, which meant, first, that he had not uttered the words, next that he did not mean them to refer to the plaintiff in his office, and that they were not defamatory of the plaintiff. He referred to the date of the meeting at which the words were uttered, viz., the 3rd December, alluded to some of the particulars which would be given in evidence, and said if the defendant really repudiated the report as given in The Mercury newspaper, it would have been easy for him to have written a letter to the newspaper, and so have denied it through the same source ; but this had not been done. He should not take up their time, but would at once proceed to call evidence.

Thomas Cooke Just, examined by Mr. Adams : I was reporter to The Mercury newspaper on 2nd December, 1867. In that capacity I attended a public meeting held on that date at the Royal Standard Inn, in Elizabeth-street. I was there in consequence of an advertisement that appeared in The Mercury newspaper. (Advertisement admitted and read.) There were about eight persons present. Some of these were Mr. Spence, Mr. Seabrook, Mr. Wiggins, Mr. Spurling, and myself, and one or two others I did not know. On that occasion Mr. Spence made a speech. I wrote out a condensed report of what he said at the time. I did not take the notes in shorthand. What I did take down was a correct report of what Mr. Spence said, except that I wrote in the third person, while he spoke in the first. Before I left the room I read a sentence, or a sentence and a half to Mr. Spence. I produce the notes I took that evening. One passage uttered by Mr. Spence struck me as peculiar, and I read it over to Mr. Spence. The passage to which I refer was:- " He referred to a quantity of timber which had come up from Port Arthur, and which had not been accounted for to the Auditor. He could tell where the timber was. He could show people the government brand on it now, and could produce carpenters who had been engaged night after night sawing off the ends of that timber." It was after the meeting, when people were moving in and out of the room that I read this passage over to Mr. Spence, and I understood him to assent to it as correct. I remember the words, " Some of these people had made £1000 out of the Bridgewater contract." Mr. Spence used those words, and I certainly understood him to mean Mr. Cheverton of the Public Works Department and others. By the expression referred to, I understood that the transaction was a questionable one. To explain what I mean by that I should have to refer to words which were spoken before. Mr. Seabrook made a speech at the meeting and he referred to it. I understood that there had been a contract for a causeway across the river at Bridgewater, and that Messrs. Cheverton and Andrews were the contractors. A Mr. Grant had been appointed superintendent of works, and he had refused to give a certificate as to the completion of the work, because the work was not properly finished. Mr. Falconer then stepped in and gave the certificate. Messrs. Cheverton and Andrews were, I believe, the contractors. I understood the certificate to have been refused by Mr. Grant because some wall was not finished. The impression left upon my mind by the words was that £1000 had been wrongfully paid to some one in consequence of Mr. Falconer having given the certificate. I presume that the thousand pounds must have been paid to the contractors. I presume that the words "some of these people" included the contractors and others. Mr. Cheverton was one of them. I understood this generally from what had transpired. My reason for thinking so was that I knew Mr. Cheverton was one of the contractors. I certainly understood from what had transpired previously that Mr. Cheverton was referred to in the words. The meeting was at eight o'clock in the evening. By the words "He had had offers made to him from that office" I understood from the Public Works Office. I remember tho expression, " Oh, Mr. Spence, say nothing about this work, and you will save us £500. If you do this you can have anything you like on the main line of road." I understood by this that Mr. Spence might have any contract on the main line of road. By the remarks of Mr. Spence in reference to a quantity of timber having come from Port Arthur and not been accounted for, and having been worked up in the Town Hall, &c., I understood that a quantity of timber had come up from Port Arthur, and that the Auditor had complained that the timber had not been accounted for. Mr. Spence had been trying to account for the missing timber. The fact is the whole matter about the timber was fresh in my memory, political capital having been made of it during the election where Dr. Crowther was concerned. Reference was also made at the meeting to Dr. Crowther in connection with the election for the city. By the words "There should be an investigation into that department, and if there was neither Falconer, Cheverton, nor Gray would be in that office," I understood that if such an investigation was made these persons would be dismissed. By the expression "we want honest men in that department," I understood precisely what the words express, namely, that they did want honest men in that department.

Cross-examined by Mr. Cansdell: The report is in accordance with the notes, which I produce; (The whole of the notes were here read.) My report is an exact account of the words, with the exception of its being in the third person instead of the first. The report was written out at the time. The speakers were not fast spoken. Had I reported all that was said it would have filled ten or twelve columns of The Mercury. It is a verbatim report of what was spoken, and reported with the exception to which I referred. I am sure the words " that office" were used. I did not understand the speaker to refer to the whole of the timber, but to part only. The words, "The money for that timber had gone into the pockets of that company" were spoken. I did not understand what was referred to by " that company." Several persons were before referred to, and I didn't know to which of them he (Spence) referred. The words " honest men" conveyed to my mind precisely what they mean. The words are ambiguous. I think they referred both to the officers and contractors. In the former part of the report the officers were alluded to. I understood them to refer to others than the officers, because Mr. Cheverton was referred to as a contractor and also as an officer. As to what was meant by the expression "honest men," the Bridgewater causeway, and other matters before referred to, influenced my mind. The expression, "We want honest men in that office" conveyed to my mind that there was corruption in the office, and that the sooner there was a change the better. The speakers evidently intended to insinuate that there was corruption, and that in the event of an investigation taking place they could bring forward such evidence as would lead to the parties named being dismissed.

The Solicitor-General said he should not call any other witness.

Mr. Cansdell now addressed the Court briefly for the defence. He expressed surprise that the learned counsel should have called only one witness. He should now call witnesses who would give a very different complexion to the case to that which had been put upon it. He referred generally to the words spoken, and said they were intended to convey a very different meaning to that put upon them. He called James Spence, defendant, who said : I was present at the meeting of contractors. I made a speech. I said some of those people have made £1000 out of the Bridgewater contract. I meant Andrews, Gowland, and Cheverton, supposed to be in company as contractors. I said this on speaking after Mr. Seabrook. He mentioned the names, and I referred to them as those parties. I had good reasons to suppose that they were in partnership. Cheverton told me he had been in partnership with Andrews, and I naturally supposed (in fact it was common rumour) that Cheverton, Andrews, and Gowland were partners. Cheverton told me in the previous year, while an officer of the department, that he was still in partnership with Audrews. He told me "he went in with a thorough understanding that he was to be a contractor, that it would not pay to give up contracting for a government situation. I never made use of the words " I have had offers made to me from that office". To my re-collection I never made use of those words. I said part of it concerning Mr. Gowland, and part concerning Mr. Cheverton. I said at the Champion Races Mr. Gowland met me behind the stand, and said " Why, Mr. Spence, that re-port of your's would cost us £500," and further that " if I would say no more about it, it would save him £500." Cheverton was standing by, and said that I should not be hot headed over the mat-ter, and that if I said nothing it would save them £500. Cheverton said I could then have any thing on the road as no other contractor could compete with me. That was the whole affair, or any-thing I over said in regard to that matter. I did not say I had received offers from " that office." I say the office had nothing whatever to do with it. In speaking about the Bridgewater Causeway, I referred to what had taken place at the time in 1863. The contractors then met and sent in a report on the work which had not been properly done. There was about £1300 worth of work unfinished. There were clauses put into the conditions which (had they not been inserted) would have made my contract for that work £1300 less than it was. I am sure I never said I had offers made from the department. Gowland said it would save him £500. I always understood Cheverton was in partnership with Gowland. When Cheverton and Gowland spoke to me I was talking of the way they had used me about another contract, and said that I was taking the action I then was in consequence, and had sent in the report. Cheverton talked about my being a fiery temper, and he said if there was no bother and I tendered in future no other contractor could compete with me. I did not mean that to be understood in my speech as an offer of a bribe. I did not say so. Cheverton had no power to give a contract. I must have been misunderstood by anyone who said I meant it to be understood that this was a bribe. I have heard the passage read in reference to the timber. I have heard about timber years ago, before 1863. In speaking about the timber, I held a paper in my hand, which showed that it had appeared in the Government Gazette that the auditor had complained that timber was not accounted for. Dr. Crowther referred to the same matter at his meetings. I said I could produce men who had sawn the ends of part of that timber, and also that another part of that timber which the auditor said he could not get an account of, had been worked up in the Town Hall. I said the money for that timber had gone into the pockets of that company. By the expression, that company, I meant Cheverton, Andrews, and Gowland. I have heard the re-porter's notes read to-day. They are not a faithful report. It can't be a fair report, because it has taken in the whole of the timber, and a great many things that I said are omitted which, coupled with what is put down, would alter the meaning. I can't exactly say what is omitted. A good deal is on the Bridgewater Causeway affair. Then, as to the expression, " If an investigation was made into these matters, neither Falconer, Cheverton, nor Gray would be in that office." I never used those words. I said " if an investigation was had into that office," and so on. The remark was not made in connexion with the timber. I never supposed either Falconer or Gray ever had anything to do with the timber. I said Cheverton was connected with the timber ; and did so from current report. I may have said, " We want honest men in that department." I don't remember it. I may have said that, meaning it in regard to contracts. I meant that the contractors required honest dealing. I had myself suffered greatly by some of these people, and considered I had not been honestly dealt with in the matter. I said we wanted men who would act fairly by us, and I considered I had not been dealt with fairly by the officers of the department. These people condemned my work in 1863, leading to a loss of £300 odd. That was where I considered we wanted honest dealing. I petitioned the Executive at the time, and charged dishonesty to the department in the petition. When I called this meeting of contractors I was influenced by rumors which I had heard concerning the plaintiff and others. I called it especially to protest against the clause requiring a £50 deposit. I was influenced in what I said by what I had heard. I have received reports for a number of years, some of them in writing, as to what was going on. These were especially against Cheverton. The general reports of the working men were that he put men on to works and took them away when he wanted them for other business. Reports also flow about as to the timber. I had reports from many. I had men who re-ported that they had carted certain timber to plaintiff's place. It was on the reports of other persons - working men - that I made the remarks which I did about the timber. I have received a report that the timber brought up by the Culloden steamer was not taken to Bridgewater, but was left at Mr. Cheverton's house at O'Brien's Bridge.

His Honor here remarked that he did not think this evidence could be received. They could not receive evidence of any rumors excepting those affecting the particular timber referred to in the speech ; and evidence of the kind was, of course, only admissible to disprove malice.

Mr. Cansdell submitted that evidence as to any timber, or shingles, or slates, or other goods having been appropriated might have affected the defendant's mind ; and as this was a slander of the plaintiff in his office he thought any such rumor would affect him, and would therefore be evidence.

His Honor pointed out that the witness had already said he made those statements in consequence of rumours which he had heard. What would be the use of introducing rumours respecting which he had made no statement?

After a few remarks Mr. Cansdell dropped the point.

Witness continued : I acted upon these rumours in the way I did believing them to be true.

Cross-examined by the Solicitor-General : I don't recollect Mr. Just reading a part of his report to me. He might have done so. I don't recollect it. I read the report of my speech in tho newspaper. I did not take steps to contradict it. I did contradict one. I sent a note to Mr. Gray. I gave my solicitor instructions to do what he thought proper in reference to the report.

I read the leading article in the newspaper on the following day. It quoted the part in reference to the timber. I took no step even then to correct the report. I went to my solicitor as soon as I received the notice, and he could have done as he liked. I could have produced carpenters who had been engaged night after night sawing off the ends of part of the timber. I could have done so if there had been a suspension of the officers. I knew a man named Lindsay who said he had cut the ends off the timber at Mr. Cheverton's farm, and also at the house at O'Brien's Bridge. I knew a laborer who had told me he had carted the timber,and had burned the ends. I never wished it to be understood that Cheverton had offered me a bribe in connection with the Bridgewater contract.

To His Honor : I never said there should be an investigation into " these matters" (meaning the timber.) I referred to other matters, and said there should be a general investigation into the office. I did not mean that the investigation should be confined to what was stated that night even. By the term " that company" in reference to the timber, I meant not the officer, of the Works Department, but the contractors for the Town Hall. By the expression, "We want honest men in that department" I meant men who would conduct the business of the department more fairly.

The witness here explained that he had meant to convey in reference to the Bridgewater causeway, that if certain clauses in reference to walls,(&c., had not been inserted in the conditions of contract afterwards, he would have tendered £1300 lower than he had done, and therefore that amount would have been saved.

To His Honor, at the request of the Solicitor-General : I did two or three days after the report appeared have a conversation with Mr. Davies. I never said the report was correct. I might have said that if an investigation was allowed I would be able to prove everything as I stated it, not as it appeared in the paper. I might have said that, but I don't recollect seeing Mr. Davies at all.

His Honor here cautioned the witness, and said he was not to give evidence as to what he might have done, but as to what he did.

His Honor : Did you have a conversation with Mr. Davies, and did you say the report was correct, and that you were prepared to prove all you had said if there was an investigation, or words to that effect ?

Witness : I might have said so had I met Mr. Davies ; but I can't recollect. Where was it ?

The Solicitor-General : In Macquarie-street at the junction of Elizabeth-street near Mr. Lord's house, on the day the leader appeared in The Mercury. That was the 4th December.

Witness : I cannot remember. I have no doubt that I might have met Mr. Davies ; but I don't remember it.

His Honor : Do you remember speaking to Mr. Davies at all on the subject of your speech ?

Witness : I don't remember.

The Solicitor-General : Now, did you not meet Mr. Davies, and thank him for doing a public good ?

Witness: Certainly not, I never thanked Mr. Davies in my life.

ln answer to Mr. Cansdell, witness further said that he made his remarks about the Bridgewater Causeway from rumors which he had heard, and also from what he had seen. e saw that the work was not finished according to the specification. The consequence of that was that he joined the other contractors in a complaint. That was what he meant when he said " some of these people had made £1,000 out of the work." He did not know that Mr. Grant had refused the final certificate till he heard Seabrook say it at the meeting. Grant was a builder by trade, and superintendent of the work.

James Pross, formerly a contractor, said: I was present at a meeting of contractors held at Mr. Spence's. I heard Spence say " some of these people had made £1,000 out of the Bridgewater causeway." I understood from that " the contractors." I can't remember him saying he had had offers proferred to him from that office. I heard him say that Cheverton and Gowland came to him at the Champion Races and said that if he said nothing about the work it would save them £500. By that I understood the contractors, Cheverton, Andrews, and Gowland. I heard Mr. Spence say that they said, " if you do this you can have anything you like on the main line of road." I understood by that that he could have any tenders for metal, and if he put in for them that he would not be molested or annoyed. I did not understand there was anything corrupt or improper in the words, or attributed to Cheverton. It did not convey to my mind that Cheverton or Gowland intended to act corruptly. I understood that if he had a contract on the road he would not be interrupted. I understood that Spence had been interrupted before in contracts on the road ; that Cheverton had refused metal supplied by him, and I understood it to mean that if Spence would hold his tongue this would not occur again. I heard the words used in regard to sawing the ends off the timber, and as to timber having been worked up in the Town Hall. I heard the words, " The money for the timber had gone into the pockets of that company." I took it that they meant the contractors. I heard the expression as to wanting honest men in the department, and I took it that they meant honest contractors. I think I heard the words that there should be an investigation into these matters. I could not swear that the words might be " into that office."

Cross-examined by Mr. Adams : I have been Mr. Spence's overseer on two contracts. I was last in his service two years ago.

Ansley Spurling : I am reporter for the Tasmanian Times, and was present at the meeting. I did not take a full report, but what is called a long-hand report, from which I wrote out afterwards. I do not think Mr. Spence said an enquiry into " these matters," but into "that public office." I believe the words, "They wanted honest men in that office," were used. They are not on my notes. My report was not a verbatim report. The words on my notes were the actual words used. They are, "We want only justice. Every public body should have faith. The contractors should now make a stand."

To the Solicitor-General : The words in the Tasmanian Times, as to the conversation on the race-course, were correct. The words taken by me were that Cheverton offered not to oppose his (Spence) on the road if he would hold his tongue about the affair. What I understood from that was that Cheverton would not tender in opposition to him. The words in the Tasmanian Times conveyed the same meaning. The witness read the part of his report having reference to the timber and the long company. He understood by those words that Mr. Spence meant the contractors for the Town Hall, Messrs. Cheverton, Andrews, and Gowland. He did not remember the expression, " They wanted honest men in that department". It might have been used.

This closed the evidence for the defence.