Professional photographer Charles Nettleton (1826-1902) worked for the Victorian police in the 1870s-1880s. He is believed to be the photographer of this carte-de-visite of bushranger Ned Kelly dated January 1874 which was attached to Kelly's Beechworth Gaol Record sheet.

Ned Kelly's prison record dated 14.3.73 (PROVic)

Link: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/edward-kelly-s-prison-records-public-record-office-victoria/GgFk8Pd6XBPZ4A

Full title: Victoria Police [44], supplementary report of criminal offence or police inquiry - with portrait of Ned Kelly [1874]

Author / Creator: Victoria Police

Author / Artists: Nettleton, Charles, 1826-1902

General note: Possibly photographed by Charles Nettleton.

Photograph is a copy of one taken by prison authorities at the end of the bushranger's second jail sentence in 1874. Nettleton was police photographer when this photograph was taken. --

Reference: The Dictionary of Australian artists : painters, sketchers, photographers and engravers to 1870 / edited by Joan Kerr. Melbourne : Oxford University Press, 1992.

The State Library of Victoria also holds a photograph of the same portrait of Ned Kelly with additional information.

View the record, Ned Kelly (Image Number: pi002398), on the State Library of Victoria's online pictures catalogue.

State Library NSW

Link: https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/YRlZvRqn

Above: Entry on Charles Nettleton pp 566-567 and entry on Thomas J. Nevin, pp 568-9

The Dictionary of Australian artists : painters, sketchers, photographers and engravers to 1870, edited by Joan Kerr.

Publisher: Melbourne : Oxford University Press, 1992.

Description: xxii, 889 p. : ill., facsims., ports. ; 27 cm.

Thomas J. Nevin, Tasmania

A similar prisoner record is held at the Penitentiary Chapel Historic Site, Tasmania, of convict Allan Williamson with Thomas J. Nevin's original carte-de-visite taken in 1875 attached:

Prison record of convict Allan Williamson with T. J. Nevin's carte

Source: eHertitage, State Library of Tasmania

Thomas J. Nevin (1842-1923) worked from his studio on government commission from 1872 to 1875 as the commercial photographer contracted to photograph prisoners for the colonial government's Attorney-General, the Hon. W. R. Giblin, his family solicitor since 1868. With the transfer of prison administration from Imperial funding in 1871, Nevin's work centred on the Mayor's Court, Hobart Town Hall, the Hobart Supreme Court and adjoining Hobart Gaol, and the Port Arthur prison on the Tasman peninsula. He also worked with detectives as bailiff for the Municipal Police in Hobart, and the Territorial Police in New Town, Tasmania. His photographic work was considered so effective in police surveillance that he was appointed full-time Office and Hall keeper to the Hobart Town Hall, which housed the Municipal Police Office (with cells), the central registry of criminal records, in January 1876. His last documented work with police was in 1888, when he ceased professional photography, the date on which his copyright absolute of 14 years on his studio trademarks expired.

The effectiveness in detecting crime with the introduction of photographing prisoners in Victoria was noted in this article:

VICTORIA

The system of taking photographic likenesses of prisoners at the Pentridge Stockade is stated to have proved of great assistance to the police department in detecting crime. The system was commenced at Pentridge about two years ago, and since then one of the officials who had a slight knowledge of the art, with the assistance of a prisoner, has taken nearly 7000 pictures, duplicates of which have been sent to all parts of this and adjacent colonies. But it has been considered rather too expensive to employ an official entirely for the purpose, and as constant employment could not be provided in the future, a photographer has lately been appointed, who will visit the stockade twice in the week, and the hulks at Williamstown once. -Argus

Source: The Pentridge photographer

Launceston Examiner, 22 August 1874, reprinted from the Argus.

The intact criminal record sheet from the Hobart Gaol bears the standard carte-de-visite mugshot in an oval mount used by T. J. Nevin and other Australian prison photographers in the 1870s. Allan Williamson was a repeat offender, an habitual criminal with a Supreme Court trial. He was photographed at the Hobart Gaol in 1875 and released with a ticket-of- leave on 12th December 1877, the earlier date being Nevin's registered photograph. Williamson re-offended, was incarcerated again at the Hobart Gaol and released on several occasions. He died in custody in 1893.

Thomas Nevin's busiest years were 1873-1880 at the Municipal Police Office and Hobart Gaol. The transfer of the majority of the criminal class of inmate at the Port Arthur (60 kms from Hobart) to the Hobart Gaol and Invalid depots began in 1871 and was effected by mid-1874. Nevin photographed these men once they had arrived in Hobart, if they had not been photographed earlier at their most recent trial at the Hobart Supreme Court. Few were photographed at Port Arthur, and those that were returned by 1874, such as William Campbell aka Job Smith, were photographed by Nevin in Hobart prior to departure. In William Campbell's case (later hanged as Job Smith), Thomas Nevin escorted him back to Port Arthur on May 8th 1874 at the request of the new Commandant, Dr. John Coverdale, just weeks after his wife Elizabeth Rachel (Day) Nevin gave birth to their second children and first-born son, Thomas James Nevin jnr (1874-1948). His father-in-law Captain James Day registered the birth in Thomas Nevin's abscence at the Port Arthur prison The majority of prisoners whose images survive in public collections today were photographed by government contractor Thomas J. Nevin at Supreme Court criminal sittings; on remand at the adjoining Hobart Gaol; during incarceration, and on discharge. The Port Arthur conduct registers repeatedly show "Transferred to the Hobart House of Correction for Males" for those men returned to Hobart between 1873 and 1875, signed by the Attorney-General.

Because of new police regulations in force from 1871 in NSW and 1873 in Victoria, following the Victorian commission into Penal Discipline Reforms in 1871 and amendments to the Police Act 1868 requiring the adoption of new police techniques of surveillance and record-keeping in Tasmania, Thomas J. Nevin was required to produce standard half plate negatives of a prisoner, printed as a mounted carte-de-visite, in addition to four to six duplicates. Those which now survive in public collections at The Mitchell Library NSW (11), the National Library of Australia (84), the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (55), the Archives Office of Tasmania (copies and duplicates, 92) and the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (112) were all correctly attributed to T. J. Nevin at accession and continue to be correctly attributed to Nevin. Although formerly believed to be some sort of ethnographic portfolio of photographs of transported exiles to Port Arthur (i.e. those who had arrived by 1853 and no later), the men in these images were not photographed because they were transportees per se, nor were they photographed at Port Arthur. Their photographs were reprised by copyists such as Beattie and Searle in the 1900s as artefacts of criminality for the middle-class gaze of the tourist to Tasmania whose visits would include a tour of Carnarvon, formerly the Port Arthur prison site, but in the 1870s, these photographs served the immediate and daily purpose for police in keeping track of habitual criminals for a central registry. These men were photographed with a booking shot on being received in Hobart on arrest, arraignment, and sentencing at the Supreme Court and Hobart Gaol, and in most cases again when were they were released to freedom with a ticket-of-leave and various other conditions from the Mayor's Court and Municipal Police Office, Town Hall where Nevin worked full-time from 1876-1880. The weekly police gazettes of the day show a record for every single man in every single extant photograph for these events during these years. The cartes-de-visite were simply produced to accompany the centrally located police office and Hobart Gaol registers by contracted photographer T. J. Nevin , and this is the original source from which they were divorced by later copyists, many removed from the blue criminal record sheet to which they were pasted.

Thomas J. Nevin was assisted by his younger brother Constable John Nevin who was salaried in administration as Gaol Messenger at the Hobart Gaol during the years 1874 -1884. The contract was issued by ther Hon. W.R. Giblin, variously Attorney-General and Premier, whose portrait Nevin took ca. 1874. The Giblin portrait by Nevin is held at the Archives Office of Tasmania; the Superintendent of Police, Richard Propsting at the Town Hall Office, the Inspector of Police John Swan, and the Sheriff at the Hobart Gaol were among Nevin's supervisors and colleagues.

Frazer Crawford, South Australia 1867

As to the technical difficulties of producing prisoner ID photographs, Frazer Smith Crawford (ca 1829 - 1890) in South Australia has left a written record of the problems as early as 1867 in this account sourced from the Art Gallery of South Australia:

"‘I have the honor to inform you that in obedience to your instructions I visited the stockade on the 21st and the gaol on the 22nd inst. and likewise consulted the Sheriff and Superintendent of Convicts as to the best method of carrying out the wishes of the Government in regard to taking photographs of the prisoners in these establishments. I found in the stockade 147 and in the gaol 110 prisoners – of these say 120 in the stockade and 70 in the gaol, in all 190, would be such characters as the Sheriff or Commissioner of Police might desire to have photographs of for police purposes.

There would be no practical difficulty supposing I had suitable apparatus in taking separate likenesses of the prisoners in either the gaol or stockade, as long as the prisoners did not object to submit to the operation. The best method to be adopted would be to take vignette portraits of them in the open air on the shady side of one of the courts, using a blanket for a background. Such portraits would be little inferior as works of art to those taken in the best lighted studios, and the work might be proceeded rapidly in fine, tolerably calm weather. A dark cell would do for a photographic dark room. As the convicts in the stockade are kept closely shaven and with their hair cut close, the likeness would not be so satisfactory as if taken in their ordinary style of [--]ing the hair, so that I would recommend that future convicts be taken at the gaol after conviction and prior to their being sent to the stockade.

The convictions average about 20 each criminal sitting ... I do not think that more than 10 negatives on the average could be taken daily, so that it would take 12 days at the stockade and 7 days at the gaol to complete taking the negatives of the present prisoners. As my assistant Mr Perry has been well accustomed to out of door photography he is quite competent to undertake these duties and I could spare him at present for a day or so occasionally without greatly interfering with the work of the photolithographic department. The negatives once taken, we could print copies from them at our leisure without interfering with our ordinary work. As the instruments used in portraiture are entirely different from those used in copying it would be necessary to purchase apparatus for the purpose such would cost between fifteen and twenty pounds. When once the prisoners in the stockade are taken such might be kept at the gaol to be used when required. The cost of printing each card picture would amount to about twopence – for chemicals, cards, etc.’

Screenshot. Source: Art Gallery of South Australia

TRANSCRIPT

GOVERNMENT PHOTO-LITHOGRAPHER

In July and August 1866 Walter William Thwaites senior discussed the possibilty of establishing a goverment photolithographic department with the Surveyor General, G.W. Goyder, hoping his son Hector James Thwaites could be employed as his assistant. Other photographers who applied for the position were Henry Anson and F.S. Crawford.

Frazer Crawford of the Adelaide Photographic Company was appointed to the position, and by December 1866 he was in Melbourne looking for the equipment needed to establish the new department, but could not find a large camera or supply of large glass plates. An order for a 16 x 18-inch camera and accessories was sent to London, and with his order for glass plates he instructed the supplier to pack them carefully, as some plates imported from England for the Adelaide Photographic Company had been spoiled ‘owing to the glass sweating on the voyage.’ Chemicals and processing equipment were ordered from Johnson & Co. of Melbourne.

On 7 December, while staying at the Globe Hotel in Swanston Street, Crawford wrote to John Noone, the newly appointed Victorian Government photo-lithographer, asking if he could ‘witness the practical details’ of Noone’s department and take ‘such notes of buildings, apparatus, &c.’ that he thought may be of use in a similar department in Adelaide. In his reply Noone said he had spent a lot of time learning the process and would not ‘impart such information unless your government is willing to remunerate me.’

When told that Crawford did not have the authority to promise remuneration Noone relented, informing Crawford that he would provide all the necessary information and leave it to the South Australian government to provide appropriate remuneration. Noone told Crawford that ‘many persons have aked me for the information I now offer to impart to you and expressed their willingness to pay for the same. Amongst others a Mr Deveril ... at Ballarat who informed me that he had made an application [for] the appointment you now hold, and who in the event of obtaining it would have been willing to pay me a considerable sum for my trouble in teaching him.’

By the end of December 1866 Crawford had been shown the process and had returned to Adelaide. He rented Freeman & Belcher’s former studio opposite the Town Hall in King William Street for a temporary photolithographic office, taking them for a period of four months from 16 February at £2 per week until a new office was built. A Mr (H.?) Perry was engaged as an assistant on a weekly salary of £3, to be paid from the labourer’s list.

One of Crawford’s first assignments was to photograph the prisoners at the stockade (Yatala) and at the Gaol. In a letter to the Surveyor General, dated 25 March 1867, Crawford wrote: ‘I have the honor to inform you that in obedience to your instructions I visited the stockade on the 21st and the gaol on the 22nd inst. and likewise consulted the Sheriff and Superintendent of Convicts as to the best method of carrying out the wishes of the Government in regard to taking photographs of the prisoners in these establishments. I found in the stockade 147 and in the gaol 110 prisoners – of these say 120 in the stockade and 70 in the gaol, in all 190, would be such characters as the Sheriff or Commissioner of Police might desire to have photographs of for police purposes. There would be no practical difficulty supposing I had suitable apparatus in taking separate likenesses of the prisoners in either the gaol or stockade, as long as the prisoners did not object to submit to the operation.

The best method to be adopted would be to take vignette portraits of them in the open air on the shady side of one of the courts, using a blanket for a background. Such portraits would be little inferior as works of art to those taken in the best lighted studios, and the work might be proceeded rapidly in fine, tolerably calm weather. A dark cell would do for a photographic dark room. As the convicts in the stockade are kept closely shaven and with their hair cut close, the likeness would not be so satisfactory as if taken in their ordinary style of [--]ing the hair, so that I would recommend that future convicts be taken at the gaol after conviction and prior to their being sent to the stockade. The convictions average about 20 each criminal sitting ... I do not think that more than 10 negatives on the average could be taken daily, so that it would take 12 days at the stockade and 7 days at the gaol to complete taking the negatives of the present prisoners.

As my assistant Mr Perry has been well accustomed to out of door photography he is quite competent to undertake these duties and I could spare him at present for a day or so occasionally without greatly interfering with the work of the photolithographic department. The negatives once taken, we could print copies from them at our leisure without interfering with our ordinary work. As the instruments used in portraiture are entirely different from those used in copying it would be necessary to purchase apparatus for the purpose such would cost between fifteen and twenty pounds. When once the prisoners in the stockade are taken such might be kept at the gaol to be used when required. The cost of printing each card picture would amount to about twopence – for chemicals, cards, &c.’ By the end of August 1867 Crawford had supplied 150 carte de visite portraits of prisoners to the Commissioner of Police.

When it was learnt that South Australia was to receive its first Royal Visit a Prince Alfred Reception Committee was formed. One of the committee’s recommendations to the Government was that a gentleman be engaged to ‘furnish a narrative of the Duke’s visit, and to be accompanied by a photographer to illustrate the events it is proposed to record.’ The committee recommended J.D. Woods as writer and suggested that Crawford, as government photographer, could take the photographs. After some discussion as to the availability of Crawford’s time and suitability of his instruments the committee was told to arrange for a private photographer. Townsend Duryea received the official appointment on 26 September 1867.

Similarly, in June 1868, when the South Australian Society of Arts asked if the Government photo-lithographer could use his large camera to copy an engraving for the Society the request was denied. The Surveyor-General noted that ‘all applications of this nature must be refused as its allowance might interfere with the business of private operators,’ even though it had been pointed out that the Government camera was the only instrument in the colony large enough to make the copy.

On 29 May 1869 a long letter from a correspondent, ‘Publico’, was published in the Register. In it Publico criticised the Government’s photo-lithographic department, calling it a white elephant and an expensive pet project of the Surveyor-General, G.W. Goyder. He claimed that the cost of the department was too high and that the work should be done by private photographers.

Crawford drafted a detailed reply to Publico’s claims and asked for permission to forward it to the Register for publication. His request was denied, and he was told by the Deputy Surveyor-General, ‘The letter which you wish to reply to, is only one out of many foolish and ignorant attacks and criticisms made by obscure persons on the Officers of this Department, and on their performance of their public duties. It is contrary to the regulations of the Service that Officers should write to the Public Papers on matters connected with their Department and in the present case while admitting the justice of your reply, I cannot sanction any departure from the established Rules.’

Frazer Crawford was over seventy years of age and still employed as Government Photolithographer when he died suddenly from heart disease at his Norwood home on 29 October 1890. His successor was his assistant, Alfred Vaughan. A Public Service Commission inquiry had earlier recommended that Vaughan be made head of the department and other work found for the aging Mr Crawford.

By the end of August 1867 Crawford had supplied 150 carte de visite portraits of prisoners to the Commissioner of Police."

Darlinghurst Gaol, NSW, 1872

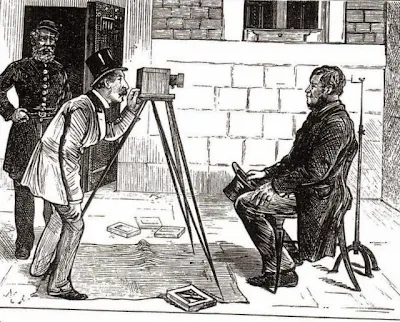

This cartoon was reprinted in Davies and Stanbury's The Mechanical Eye in Australia (1985, page 201).

Cartoon of prison photographers from the Illustrated London News, 1873, reprinted in The Mechanical Eye in Australia (OUP, Davies & Stanbury, 1985.

Accompanying the cartoon is a long quotation from the Sydney Morning Herald of the 10th January 1872 in which the reporter describes the recently introduced English practice of photographing prisoners taking place at the Darlinghurst Goal. The authors Davies and Stanbury added this last observation with a footnote:

"Cartes-de-visite of convicts taken at Port Arthur in 1873-1874, possibly by the Commandant, A.H. Boyd [footnote 3], survive in the Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston, and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart."

[Footnote 3 says: "Letter from Chris Long, formerly at Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston."]

Chris Long sent out a few such letters. Notice the wording:

"possibly by the Commandant A.H. Boyd ..." .Chris Long was the first and the last to suggest such a "possibility". His flight of fancy about Boyd centred on nothing more substantial than these three scraps of largely unrelated "information" proposed as "evidence" (Tasmanian Photographers 1840-1940: A Directory, TMAG 1995:36):

- a sentence in an unpublished three pages of FICTION, a children's tale about a holiday at Port Arthur delivered by Boyd's niece E.M. Hall in the 1930s which mentions neither a darkroom (Long's embellishment), nor Boyd by name nor the photographing of prisoners;

- some glass negatives allegedly sent to Port Arthur in 1873, as if these same negatives just happen to be those on which were printed these same extant images of prisoners, when a thousand negatives and prisoner photographs were in existence in Tasmania in the 1870s, and those which have survived are random estrays of a much larger corpus, now lost or destroyed;

- the ownership of a photograph tent and stand allegedly sent from Port Arthur to Hobart in April 1874 - ownership he concludes was Boyd's, but examination of the original document (Tasmanian Papers Ref: 320, Mitchell Library SLNSW) cannot support even this claim of ownership, let alone the quantum leap to attributing Boyd as a professional prison photographer where no body of work or reputation ever existed for such a claim, and no official or historical record exists that associates A. H. Boyd with either the mandate or the skills to personally take prisoners' photographs. The Boyd misattribution has wasted the time and effort of a generation of historians with an interest in forensics and police photography. Chris Long later blamed difficulties with his editor Gillian Winter (1995) and rumours spread by A. H. Boyd's descendants for publishing the furphy.

Victoria and NSW State Archives

The Public Archives of Victoria has a comprehensive range of police registers and prisoner identification photographs dating from the 1860s. This is one example, taken in 1877:

Taken in 1877 of prisoner Joseph Ralph Smith,

Central Register of Male Prisoners, PRO Victoria

Some of the Victorian mugshots taken in the late 1870s were not mounted as cdv portraits, yet the practice of printing the final carte in an oval mount which was pasted to the criminal record continued into the 1880s in Tasmanian and NSW. From ca. 1888, the Bertillon method - a square front and profile pair of photographs - replaced this practice in all Australian States.

The prison record (below) of George Miller, taken on 25th June, 1881 in a NSW gaol, closely resembles the mid 1870s genre evident in Nevin's Tasmanian prisoner ID photographs in matters of pose, vignette framing, background and processing. This document abounds with numbers - No.2688 is the prison record number at top left; 219 looks like an archivist's recent catalogue number; and ????-82 appears above the photo. The practice of photographing prisoners in NSW gaols was standard procedure before 1881, given the printed format: above the photo is printed "Date when Portrait was taken ... " and below the photo is printed "No. of previous Portrait ...".

The prisoner was convicted as early as July 1872 for drunkenness, but no previous portrait was recorded.

Gaol Photograph of George Miller [NRS 2138 Vol. 3/6044 Photo No. 2688 p. 219]

Unattributed photo: NSW State Archives

RELATED POSTS main weblog